Unforgiven: A Fistful of EVIL Dollars

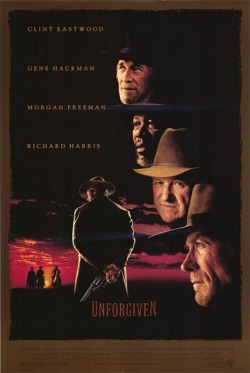

Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven came out in 1992. It won the Oscar for Best Picture, Best Director (Eastwood), Best Supporting Actor (Gene Hackman), and Best Editing (Joel Cox). It is one of the best movies ever made, but very few understand it except, maybe, a few French cinéphiles.

Some months after Unforgiven had won Eastwood the Oscar, I decided to go see it in one of Paris’s many cinématheques (I was living there at the time). As we know, expectations have a lot to do with how we react to movies. Eastwood’s symbolic tale of a retired murderer/thief who joins up with two other miscreants to earn a $1,000 bounty had been almost universally written up as a revisionist Western—as a film that flaunted the conventions of classic Westerns—so that’s what I expected. But as William Munny (Clint Eastwood) gunned down his enemies in the film’s climactic shoot-out, I felt a vague uneasiness. Sure, the film had critiqued killing, but the last scene was a celebration of righteous revenge in the best tradition of the Classic Western; and it was consistent with Eastwood’s oeuvre, culminating with a line worthy of a Buddhist tenet, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.”

I exited the theatre, trying to make sense of David Webb People’s brilliant script. Unforgiven seemed all of a piece, but at the same time appeared contradictory; it was intensely intelligent in its dissection of the myths of the genre, yet it celebrated the very things it put to shame. Sheriff Bill, Munny, the “Schofield Kid,” Ned, Munny’s kids—heck, practically everyone in the film—discusses at one time or another the chaotic logistics and shame involved in killing another human being. But when William Munny goes up against a room full of enemies, he guns them down in true Shane style, with absolutely no remorse, even though his rifle, realistically, misfires. This film was having its cake and eating it, too. Fortunately, F. Scott Fitzgerald came to the rescue.

Somewhere the author wrote, and I’m paraphrasing, “A true genius can hold two opposite points of view at the same time.” (Since then I’ve been told that something like this is also and previously stated in the Kabbalah.) A thought like that might explain how Unforgiven can be so satisfying: It is one of the few films to get away with having two contrasting points of view simultaneously. Something like how only soldiers can be genuine pacifists. But I digress. I was speaking about the French.

Fitzgerald’s genius was only a band-aid. For the film’s killing, not killing, meditations on murder, and so on, are not really the film’s raison d’etre. Unforgiven also contains perhaps a half-dozen other themes that one could write about: redemption, gun control, aging, memory, class, politics, and so on. But it wasn’t till I was reading through a list of film festivals in Paris some weeks later that I ran across something that finally put me on the right trail: Unforgiven was being included in a Marxist Film Festival. Nothing big, but one of those little retrospectives that seem to be occurring constantly in some of Paris’s 5eme arrondissement art-house cinemas. I asked myself, “Eastwood as Marxist?” Could Unforgiven have a subtext that American reviewers had missed, but that some rebellious Gauls had understood?

Unforgiven definitely depicts a world freaked out by an obsession with cash. Its point of view isn’t exactly Marxist, but isn’t exactly advocating the free market either. In fact, nearly every action in the film, however noble its inspiration, is ultimately perverted by an economic system founded on desperation. The film’s opposite numbers are both named after cash: William Munny (money) and Sheriff Bill (dollar bill). More tellingly, the film begins by setting up two distinct kinds of relationships: non-material and material. Its introductory text reads over a lone farmhouse and a tombstone:

“She was a comely young woman and not without prospects. Therefore it was heartbreaking to her mother that she would enter into marriage with William Munny, a known thief and murderer, a man of notoriously vicious and intemperate disposition. When she died, it was not at his hands as her mother might have expected, but of smallpox. That was 1878.”

A beautiful young woman dismisses her prospects (money) and marries for love. Apparently, it is a happy marriage till her death. The film then moves to the town of Big Whiskey, where it is raining and where a man is beating up a prostitute. Already a loveless business arrangement, the cowboy is making things worse. His partner holds Delilah (Anna Levine), who has laughed at the size of the cowboy’s “pecker,” while the aggressor slashes her face with a knife. Skinny (Anthony James), the owner of the bar and the prostitute’s pimp, breaks things up and calls the sheriff—and that’s when the film starts its inexorable trip to hell.

After his arrival in the saloon, Sheriff Bill (Gene Hackman) demonstrates what justice is like when it is polluted by money. His mistake at the outset is to listen to Skinny, who is at pains to point out the financial implications generated by creating an unmarketable whore: “This here’s a lawful contract [between himself and Delilah]… I got a contract that represents an investment in capital.”

“Property”, the sheriff replies.

“Damaged property”, Skinny corrects.

Taking his cue from Skinny, the sheriff decides that the offending cowboy and his partner can literally pay for their crime by giving Skinny some horses. The other prostitutes, led by Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), blow a fuse. They wanted Biblical-style punishment, an eye for an eye: i.e., “a whippin.’”

Nevertheless, the prostitutes understand the economics of the situation and so they pool their financial resources and offer a reward of $1,000 for anyone who will kill the two cowboys.

The creation of the reward caps a series of scenes in which love and justice are perverted by the laws of the marketplace—ultimately, people have been turned into objects. As Strawberry Alice observes, “Just because we let them smelly fools ride us like horses, don’t mean we gotta let them brand us like horses. Maybe we ain’t nothin’ but whores, but we—my God!—we ain’t horses!”

By giving in to purely economic reasoning, Sheriff Bill opens the gates of Big Whiskey to the demons of the marketplace. The deadliest arrival will be William Munny, who is literally the incarnation of cash—an avenging anti-hero like Eastwood’s character in PaleRider, who is called up by a girl’s prayer, or like the phantom spirit in High Plains Drifter (both films were directed by Eastwood). Even Dirty Harry, though directed by Don Siegel, often equates the detective with religious imagery.

So, as word of the reward goes out, bounty hunters come in, notably the Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett). It’s the Kid who informs Munny of the reward. William Munny is an ex-gunslinger, ex-psychopath, ex-drunk living on a pig farm in the middle of nowhere with two kids, some increasingly sick hogs, and a dead wife named Claudia (she of the opening text). Munny at first refuses the Kid’s invitation—but, as the latter remarks, the former doesn’t look too “prosperous.” Eventually, the dire economic circumstances of his farm compel Munny to ride after the Kid. Munny also sees the hunt for the bounty in chivalric terms—the defense of helpless women—but his chivalry is sickened by the promise of financial gain.

On his way after the Kid, Munny enlists the aid of an old partner, Ned (Morgan Freeman). Munny persuades Ned to come along by extolling those chivalric virtues: a woman has been disfigured and it’s their job to extract revenge, and get paid.

Back in Big Whiskey, the prostitutes continue to prove that behavior once compromised by economics is ugly to witness. When the two cowboys arrive with horses—and one in particular for Delilah, which had not been asked for by the sheriff—Strawberry Alice violently rejects them. Though the gentler of the two cowboys has tried to transform the horse from property into a sincere gesture, Alice still believes she and her colleagues are being equated with material goods. Following Alice’s lead, the whores all throw rocks at the cowboys—while hung on the building behind them, as explanation, a giant sign reads, “MERCANTILE.”

The scene switches to Sheriff Bill, who’s working on his house. Not surprisingly, given that the representative of law can’t balance the scales of justice, his house is lopsided. The leaky house is an exteriorization of his inner shortcomings—a point driven home by the fact that he’s working on his house when Skinny informs him of the reward for $1,000 for the death of the two cowboys—a reward made possible by his inability to be just.

English Bob (Richard Harris) is next to appear in the film. Whereas Munny and Ned have at least persuaded themselves that they’re fighting for a higher good, ol’ Bob is a professional killer who only recently stopped working for the railroad as an eliminator of uncooperative Chinese immigrant workers. He brings W.W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek) in tow, a biographer hoping to cash in, literally, on Bob’s violent career. (And a "bob" is an English currency unit. Thanks to reader James Campbell for reminding me of that.)

On a train, Bob first shoots birds at a dollar a kill, but his efforts at bounty hunting in Big Whiskey are less successful. Sheriff Bill disarms him and, with the American flag fluttering behind him (it’s the fourth of July), proceeds to kick his teeth out. Later when Beauchamp is explaining to the sheriff why his written version of Bob’s exploits differs from reality as Bill remembers them, Beauchamp says that one is apt to exaggerate in the publishing business “for reasons involving the marketplace.” In Unforgiven, even reality is distorted by the genius of cash.

The English Bob section of Unforgiven puts into stark relief the Americanism of Big Whiskey, which like most towns in Westerns is meant to be a microcosm of the whole country. As he leaves broken and bloodied, English Bob screams out, “Without morals or laws… It’s no wonder you all emigrated to America…a bunch of bloody savages.” Bob’s tirade does point out the uniqueness of the American experiment. Without royalty (Bob’s biography is even entitled, The Duke of Death), without the semblance of rulers appointed by heaven, can a people live in a civilized way based solely on laws? Unforgiven’s answer is no—if the laws are corrupted by money.

In one of the film’s many great shots, a train carrying the departing English Bob crosses the path of Munny, Ned, and the Kid as they ride into Big Whiskey under a downpour. Without going into details, suffice to say that the trio’s plans go slightly awry once they arrive. Munny is almost kicked to death by Bill, but recovers. They then kill the more innocent cowboy, which triggers Ned’s departure. Munny and the Kid then kill the guiltier cowboy while he’s on the toilet.

Meanwhile, Ned is picked up by Sheriff Bill and then whipped to death. A black man is whipped to death by a white sheriff, in the “Rodney King scene” as Morgan Freeman called it. Ned’s color is never referred to explicitly in the film, but the image speaks loudly and clearly. Only a mercantile system that treats people as objects could allow the slavery (and mass murder) of African-Americans. Morgan Freeman has correctly named the scene for what it is. In a film that shows the evil of beings perverted by lucre, the death of the film’s only black man is axiomatic.

High on a hill, ignorant of Ned’s fate, Munny and the Kid discuss murder as they await the delivery of their pay. Munny says, “It’s a hell of a thing, killin’ a man. You take away all he’s got—and all he’s ever gonna have.” At first glance, this might sound like heavy thinking. On closer examination, though, Munny is simply defining human life in terms of having: “all he has” and “all he’s ever gonna have.” You don’t have to go far to find more sophisticated definitions of mortality.

The Schofield Kid, however, decides he’s had enough of having. What about buying yourself those glasses you need, Munny asks. “I guess I’d rather be blind and ragged than dead,” he responds. The Kid abandons his formula of violence-equals-wealth. Sadly, the alternative is poverty. His “vision” of the world is literally skewered by economics.

A prostitute then arrives on the hill with their money. What Munny didn’t know, the prostitute tells him: Ned is dead, killed by the sheriff. As the prostitute informs Munny of how Ned was killed, he begins taking swigs from a bottle. Munny has already stated in the film that he was drunk during much of his previous killing, before he married, but he has very carefully avoided drinking up to this point in the film. After leaving the money with the Kid, Munny rides down the hill and throws his empty bottle in the mud as rides into town. The bottle is the required passport needed to enter a town named Big Whiskey. Indeed, as he rides through the town, we hear Sheriff Bill discussing how much of the posse’s alcohol intake the state will subsidize. Clearly, to perpetrate violence one needs to be numbed—and a violent state founded on violent economics is only too happy to subsidize the drinking/violence.

Munny rides by his dead friend exposed like cheap merchandise in the street. His look clearly states that, presently, those who live by money are going to die by Munny. He enters the inn as the others carouse and he slowly lowers his rifle. As they one by one realize what’s transpiring, the rooms grow silent in what is one of cinema’s great scenes.

“Who’s the fella owns this shit-hole?” Munny asks, getting right to the heart of the system.

“I own this establishment. Bought it from Greely for a thousand dollars,” replies Skinny, moving forward.

The purchase price is the exact amount of the bounty offered by the women; the circle is complete. Without further ado, Munny blasts a hole in Skinny. “You just shot an unarmed man,” Little Bill complains, his tin-plated sense of justice disturbed.

“Well he shoulda armed himself if he’s gonna decorate his inn with my friend,” Munny counters, deftly pointing out that if you’re going to treat people as objects, violence is inevitable.

Bill isn’t a coward, though, and instructs the others to shoot down Munny as soon as he uses his last barrel on Bill. An empty click. “Misfire,” cries Bill—but Munny simply pulls his pistol out and cold-bloodedly guns down every man who poses a threat, including Bill. The room clears out and Munny strides to the bar for a chaser. After Munny’s exchange with Beauchamp, who then flees, we see that Little Bill isn’t dead and that he’s preparing to shoot Munny. Bill cocks his gun; Munny hears the sound, turns, and pins Bill’s wrist to the floor with his boot. The sheriff stares up at Munny’s shotgun, which is now aimed point-blank at his head, and says, “I don’t deserve this—to die like this. I was building a house.” Bill’s last words recall his crooked house and his crooked application of justice. His words also recall Strawberry Alice’s complaint at the outset of the film—“It ain’t fair, Little Bill. It ain’t fair!”

What Strawberry Alice and Little Bill have failed to notice is that, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it,” the words that Munny now speaks just before he blows Bill’s head off.

Little Bill’s essential error is to assume that by distributing justice as if it were merchandise, by assigning monetary values to people and brutally enforcing a few random laws, that some sort of equitable system will be the result—that fairness will exist. But deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it. What happens in this world is beyond dollars and cents. Bill and Alice are stuck in a mathematical hell imposed by rigid economics: this costs that, he’s worth this much, she’s worth that much, etc.

Munny, meanwhile, stands for something else, as the introduction makes explicit: He didn’t deserve his wife’s love, but he got it. Munny is yin to Bill’s yang, and so it’s no surprise that when he strolls out of the saloon into the downpour that he takes the sheriff’s place in front of the American flag: (long shot of Munny on horse) “You better bury Ned right! Better not cut up or otherwise harm no more whores—or [cut to Munny with flag behind him] I’ll come back and kill every one of you sons of bitches.”

In traditional Western style, Munny then slowly rides out of the cleansed town. Finally, Munny is no Marxist. He comes up with no alternative to Sheriff Bill’s perverted mercantile justice, except to terrify people into doing what is right. Munny is an angry spirit. He is Dirty Harry without the constraints of a legal system. When push comes to shove, this type of character would probably prefer a world without governments or systems of any kind—a world where people spontaneously do what is right. A fantasy—but a noble one.

(Text copyright 2010 by J. W. Rinzler; Film stills copyright Warner Bros.)

Some months after Unforgiven had won Eastwood the Oscar, I decided to go see it in one of Paris’s many cinématheques (I was living there at the time). As we know, expectations have a lot to do with how we react to movies. Eastwood’s symbolic tale of a retired murderer/thief who joins up with two other miscreants to earn a $1,000 bounty had been almost universally written up as a revisionist Western—as a film that flaunted the conventions of classic Westerns—so that’s what I expected. But as William Munny (Clint Eastwood) gunned down his enemies in the film’s climactic shoot-out, I felt a vague uneasiness. Sure, the film had critiqued killing, but the last scene was a celebration of righteous revenge in the best tradition of the Classic Western; and it was consistent with Eastwood’s oeuvre, culminating with a line worthy of a Buddhist tenet, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it.”

I exited the theatre, trying to make sense of David Webb People’s brilliant script. Unforgiven seemed all of a piece, but at the same time appeared contradictory; it was intensely intelligent in its dissection of the myths of the genre, yet it celebrated the very things it put to shame. Sheriff Bill, Munny, the “Schofield Kid,” Ned, Munny’s kids—heck, practically everyone in the film—discusses at one time or another the chaotic logistics and shame involved in killing another human being. But when William Munny goes up against a room full of enemies, he guns them down in true Shane style, with absolutely no remorse, even though his rifle, realistically, misfires. This film was having its cake and eating it, too. Fortunately, F. Scott Fitzgerald came to the rescue.

Somewhere the author wrote, and I’m paraphrasing, “A true genius can hold two opposite points of view at the same time.” (Since then I’ve been told that something like this is also and previously stated in the Kabbalah.) A thought like that might explain how Unforgiven can be so satisfying: It is one of the few films to get away with having two contrasting points of view simultaneously. Something like how only soldiers can be genuine pacifists. But I digress. I was speaking about the French.

Fitzgerald’s genius was only a band-aid. For the film’s killing, not killing, meditations on murder, and so on, are not really the film’s raison d’etre. Unforgiven also contains perhaps a half-dozen other themes that one could write about: redemption, gun control, aging, memory, class, politics, and so on. But it wasn’t till I was reading through a list of film festivals in Paris some weeks later that I ran across something that finally put me on the right trail: Unforgiven was being included in a Marxist Film Festival. Nothing big, but one of those little retrospectives that seem to be occurring constantly in some of Paris’s 5eme arrondissement art-house cinemas. I asked myself, “Eastwood as Marxist?” Could Unforgiven have a subtext that American reviewers had missed, but that some rebellious Gauls had understood?

Unforgiven definitely depicts a world freaked out by an obsession with cash. Its point of view isn’t exactly Marxist, but isn’t exactly advocating the free market either. In fact, nearly every action in the film, however noble its inspiration, is ultimately perverted by an economic system founded on desperation. The film’s opposite numbers are both named after cash: William Munny (money) and Sheriff Bill (dollar bill). More tellingly, the film begins by setting up two distinct kinds of relationships: non-material and material. Its introductory text reads over a lone farmhouse and a tombstone:

“She was a comely young woman and not without prospects. Therefore it was heartbreaking to her mother that she would enter into marriage with William Munny, a known thief and murderer, a man of notoriously vicious and intemperate disposition. When she died, it was not at his hands as her mother might have expected, but of smallpox. That was 1878.”

A beautiful young woman dismisses her prospects (money) and marries for love. Apparently, it is a happy marriage till her death. The film then moves to the town of Big Whiskey, where it is raining and where a man is beating up a prostitute. Already a loveless business arrangement, the cowboy is making things worse. His partner holds Delilah (Anna Levine), who has laughed at the size of the cowboy’s “pecker,” while the aggressor slashes her face with a knife. Skinny (Anthony James), the owner of the bar and the prostitute’s pimp, breaks things up and calls the sheriff—and that’s when the film starts its inexorable trip to hell.

After his arrival in the saloon, Sheriff Bill (Gene Hackman) demonstrates what justice is like when it is polluted by money. His mistake at the outset is to listen to Skinny, who is at pains to point out the financial implications generated by creating an unmarketable whore: “This here’s a lawful contract [between himself and Delilah]… I got a contract that represents an investment in capital.”

“Property”, the sheriff replies.

“Damaged property”, Skinny corrects.

Taking his cue from Skinny, the sheriff decides that the offending cowboy and his partner can literally pay for their crime by giving Skinny some horses. The other prostitutes, led by Strawberry Alice (Frances Fisher), blow a fuse. They wanted Biblical-style punishment, an eye for an eye: i.e., “a whippin.’”

Nevertheless, the prostitutes understand the economics of the situation and so they pool their financial resources and offer a reward of $1,000 for anyone who will kill the two cowboys.

The creation of the reward caps a series of scenes in which love and justice are perverted by the laws of the marketplace—ultimately, people have been turned into objects. As Strawberry Alice observes, “Just because we let them smelly fools ride us like horses, don’t mean we gotta let them brand us like horses. Maybe we ain’t nothin’ but whores, but we—my God!—we ain’t horses!”

By giving in to purely economic reasoning, Sheriff Bill opens the gates of Big Whiskey to the demons of the marketplace. The deadliest arrival will be William Munny, who is literally the incarnation of cash—an avenging anti-hero like Eastwood’s character in PaleRider, who is called up by a girl’s prayer, or like the phantom spirit in High Plains Drifter (both films were directed by Eastwood). Even Dirty Harry, though directed by Don Siegel, often equates the detective with religious imagery.

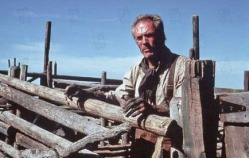

So, as word of the reward goes out, bounty hunters come in, notably the Schofield Kid (Jaimz Woolvett). It’s the Kid who informs Munny of the reward. William Munny is an ex-gunslinger, ex-psychopath, ex-drunk living on a pig farm in the middle of nowhere with two kids, some increasingly sick hogs, and a dead wife named Claudia (she of the opening text). Munny at first refuses the Kid’s invitation—but, as the latter remarks, the former doesn’t look too “prosperous.” Eventually, the dire economic circumstances of his farm compel Munny to ride after the Kid. Munny also sees the hunt for the bounty in chivalric terms—the defense of helpless women—but his chivalry is sickened by the promise of financial gain.

On his way after the Kid, Munny enlists the aid of an old partner, Ned (Morgan Freeman). Munny persuades Ned to come along by extolling those chivalric virtues: a woman has been disfigured and it’s their job to extract revenge, and get paid.

Back in Big Whiskey, the prostitutes continue to prove that behavior once compromised by economics is ugly to witness. When the two cowboys arrive with horses—and one in particular for Delilah, which had not been asked for by the sheriff—Strawberry Alice violently rejects them. Though the gentler of the two cowboys has tried to transform the horse from property into a sincere gesture, Alice still believes she and her colleagues are being equated with material goods. Following Alice’s lead, the whores all throw rocks at the cowboys—while hung on the building behind them, as explanation, a giant sign reads, “MERCANTILE.”

The scene switches to Sheriff Bill, who’s working on his house. Not surprisingly, given that the representative of law can’t balance the scales of justice, his house is lopsided. The leaky house is an exteriorization of his inner shortcomings—a point driven home by the fact that he’s working on his house when Skinny informs him of the reward for $1,000 for the death of the two cowboys—a reward made possible by his inability to be just.

English Bob (Richard Harris) is next to appear in the film. Whereas Munny and Ned have at least persuaded themselves that they’re fighting for a higher good, ol’ Bob is a professional killer who only recently stopped working for the railroad as an eliminator of uncooperative Chinese immigrant workers. He brings W.W. Beauchamp (Saul Rubinek) in tow, a biographer hoping to cash in, literally, on Bob’s violent career. (And a "bob" is an English currency unit. Thanks to reader James Campbell for reminding me of that.)

On a train, Bob first shoots birds at a dollar a kill, but his efforts at bounty hunting in Big Whiskey are less successful. Sheriff Bill disarms him and, with the American flag fluttering behind him (it’s the fourth of July), proceeds to kick his teeth out. Later when Beauchamp is explaining to the sheriff why his written version of Bob’s exploits differs from reality as Bill remembers them, Beauchamp says that one is apt to exaggerate in the publishing business “for reasons involving the marketplace.” In Unforgiven, even reality is distorted by the genius of cash.

The English Bob section of Unforgiven puts into stark relief the Americanism of Big Whiskey, which like most towns in Westerns is meant to be a microcosm of the whole country. As he leaves broken and bloodied, English Bob screams out, “Without morals or laws… It’s no wonder you all emigrated to America…a bunch of bloody savages.” Bob’s tirade does point out the uniqueness of the American experiment. Without royalty (Bob’s biography is even entitled, The Duke of Death), without the semblance of rulers appointed by heaven, can a people live in a civilized way based solely on laws? Unforgiven’s answer is no—if the laws are corrupted by money.

In one of the film’s many great shots, a train carrying the departing English Bob crosses the path of Munny, Ned, and the Kid as they ride into Big Whiskey under a downpour. Without going into details, suffice to say that the trio’s plans go slightly awry once they arrive. Munny is almost kicked to death by Bill, but recovers. They then kill the more innocent cowboy, which triggers Ned’s departure. Munny and the Kid then kill the guiltier cowboy while he’s on the toilet.

Meanwhile, Ned is picked up by Sheriff Bill and then whipped to death. A black man is whipped to death by a white sheriff, in the “Rodney King scene” as Morgan Freeman called it. Ned’s color is never referred to explicitly in the film, but the image speaks loudly and clearly. Only a mercantile system that treats people as objects could allow the slavery (and mass murder) of African-Americans. Morgan Freeman has correctly named the scene for what it is. In a film that shows the evil of beings perverted by lucre, the death of the film’s only black man is axiomatic.

High on a hill, ignorant of Ned’s fate, Munny and the Kid discuss murder as they await the delivery of their pay. Munny says, “It’s a hell of a thing, killin’ a man. You take away all he’s got—and all he’s ever gonna have.” At first glance, this might sound like heavy thinking. On closer examination, though, Munny is simply defining human life in terms of having: “all he has” and “all he’s ever gonna have.” You don’t have to go far to find more sophisticated definitions of mortality.

The Schofield Kid, however, decides he’s had enough of having. What about buying yourself those glasses you need, Munny asks. “I guess I’d rather be blind and ragged than dead,” he responds. The Kid abandons his formula of violence-equals-wealth. Sadly, the alternative is poverty. His “vision” of the world is literally skewered by economics.

A prostitute then arrives on the hill with their money. What Munny didn’t know, the prostitute tells him: Ned is dead, killed by the sheriff. As the prostitute informs Munny of how Ned was killed, he begins taking swigs from a bottle. Munny has already stated in the film that he was drunk during much of his previous killing, before he married, but he has very carefully avoided drinking up to this point in the film. After leaving the money with the Kid, Munny rides down the hill and throws his empty bottle in the mud as rides into town. The bottle is the required passport needed to enter a town named Big Whiskey. Indeed, as he rides through the town, we hear Sheriff Bill discussing how much of the posse’s alcohol intake the state will subsidize. Clearly, to perpetrate violence one needs to be numbed—and a violent state founded on violent economics is only too happy to subsidize the drinking/violence.

Munny rides by his dead friend exposed like cheap merchandise in the street. His look clearly states that, presently, those who live by money are going to die by Munny. He enters the inn as the others carouse and he slowly lowers his rifle. As they one by one realize what’s transpiring, the rooms grow silent in what is one of cinema’s great scenes.

“Who’s the fella owns this shit-hole?” Munny asks, getting right to the heart of the system.

“I own this establishment. Bought it from Greely for a thousand dollars,” replies Skinny, moving forward.

The purchase price is the exact amount of the bounty offered by the women; the circle is complete. Without further ado, Munny blasts a hole in Skinny. “You just shot an unarmed man,” Little Bill complains, his tin-plated sense of justice disturbed.

“Well he shoulda armed himself if he’s gonna decorate his inn with my friend,” Munny counters, deftly pointing out that if you’re going to treat people as objects, violence is inevitable.

Bill isn’t a coward, though, and instructs the others to shoot down Munny as soon as he uses his last barrel on Bill. An empty click. “Misfire,” cries Bill—but Munny simply pulls his pistol out and cold-bloodedly guns down every man who poses a threat, including Bill. The room clears out and Munny strides to the bar for a chaser. After Munny’s exchange with Beauchamp, who then flees, we see that Little Bill isn’t dead and that he’s preparing to shoot Munny. Bill cocks his gun; Munny hears the sound, turns, and pins Bill’s wrist to the floor with his boot. The sheriff stares up at Munny’s shotgun, which is now aimed point-blank at his head, and says, “I don’t deserve this—to die like this. I was building a house.” Bill’s last words recall his crooked house and his crooked application of justice. His words also recall Strawberry Alice’s complaint at the outset of the film—“It ain’t fair, Little Bill. It ain’t fair!”

What Strawberry Alice and Little Bill have failed to notice is that, “Deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it,” the words that Munny now speaks just before he blows Bill’s head off.

Little Bill’s essential error is to assume that by distributing justice as if it were merchandise, by assigning monetary values to people and brutally enforcing a few random laws, that some sort of equitable system will be the result—that fairness will exist. But deserve’s got nothin’ to do with it. What happens in this world is beyond dollars and cents. Bill and Alice are stuck in a mathematical hell imposed by rigid economics: this costs that, he’s worth this much, she’s worth that much, etc.

Munny, meanwhile, stands for something else, as the introduction makes explicit: He didn’t deserve his wife’s love, but he got it. Munny is yin to Bill’s yang, and so it’s no surprise that when he strolls out of the saloon into the downpour that he takes the sheriff’s place in front of the American flag: (long shot of Munny on horse) “You better bury Ned right! Better not cut up or otherwise harm no more whores—or [cut to Munny with flag behind him] I’ll come back and kill every one of you sons of bitches.”

In traditional Western style, Munny then slowly rides out of the cleansed town. Finally, Munny is no Marxist. He comes up with no alternative to Sheriff Bill’s perverted mercantile justice, except to terrify people into doing what is right. Munny is an angry spirit. He is Dirty Harry without the constraints of a legal system. When push comes to shove, this type of character would probably prefer a world without governments or systems of any kind—a world where people spontaneously do what is right. A fantasy—but a noble one.

(Text copyright 2010 by J. W. Rinzler; Film stills copyright Warner Bros.)