The Jaws Blog

Foreword

When I first saw Jaws back in 1975, I was only 12, but I knew that I’d experienced a movie unlike anything before. Jaws penetrated my inner psyche—not just because the shark was scary, but because the film was so fluid, so exciting to watch. I knew that whoever directed it should be tracked; his future films would be worth seeing, too.

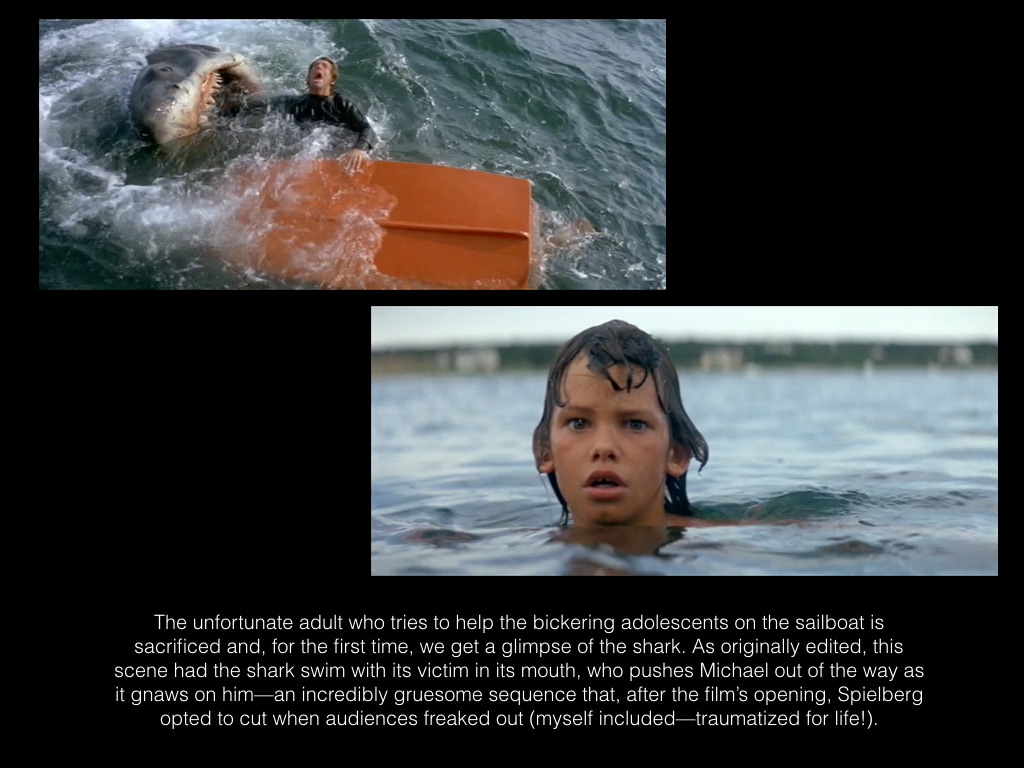

I was one of the few who saw the uncut, more gruesome version of Jaws when it opened in Los Angeles. For years, I wasn’t sure if I was imagining things, but on subsequent viewings it always seemed like the scene in which Michael and his friends are attacked in the “pond” was shorter (I still seem remember more kids being killed, but that may be a trick of memory). Finally, various publications and DVD releases confirmed that the scene had been recut and toned down. (I'm pretty sure the autopsy scene was longer and more gruesome, too.) No matter. Its effect on me was long-lasting.

As it happened, I’d seen Sugarland Express, Spielberg’s previous feature film, by accident. Going forward, I never missed a Spielberg production. They were events. Even as his high-caliber output was unrivaled--Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark—adults around me considered Jaws to be sensationalistic film fluff. After all, the story was pretty bare-bones: A shark eats several inhabitants of Amity, so a police chief has to rid the seas of the shark. But as a kid, I understood instinctively that it and Spielberg’s other films weren’t only about content—they were about the kinetic experience itself of film: the composition, editing, music, and all the things that go into a movie if you’re doing it right. To some extent, style is content. And Jaws was one hell of a style, an artistic achievement. Indeed, during those years, Spielberg was one of the most exuberant, inventive filmmakers in the history of cinema. Only Kubrick and Hitchcock come to mind as comparable Hollywood directors. Interestingly, Hitchcock’s later period segues into Spielberg and overlaps: Psycho (1960) and The Birds (1961) had prepared the terrain for Jaws. The last film directed by the Master of Suspense, Family Plot (1976), came out a year after Jaws.

Then Spielberg slowly but surely became more acceptable in the eyes of grown-ups and critics. The Color Purple had an ambivalent reception, as did Empire of the Sun, but Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan made him respectable worldwide.

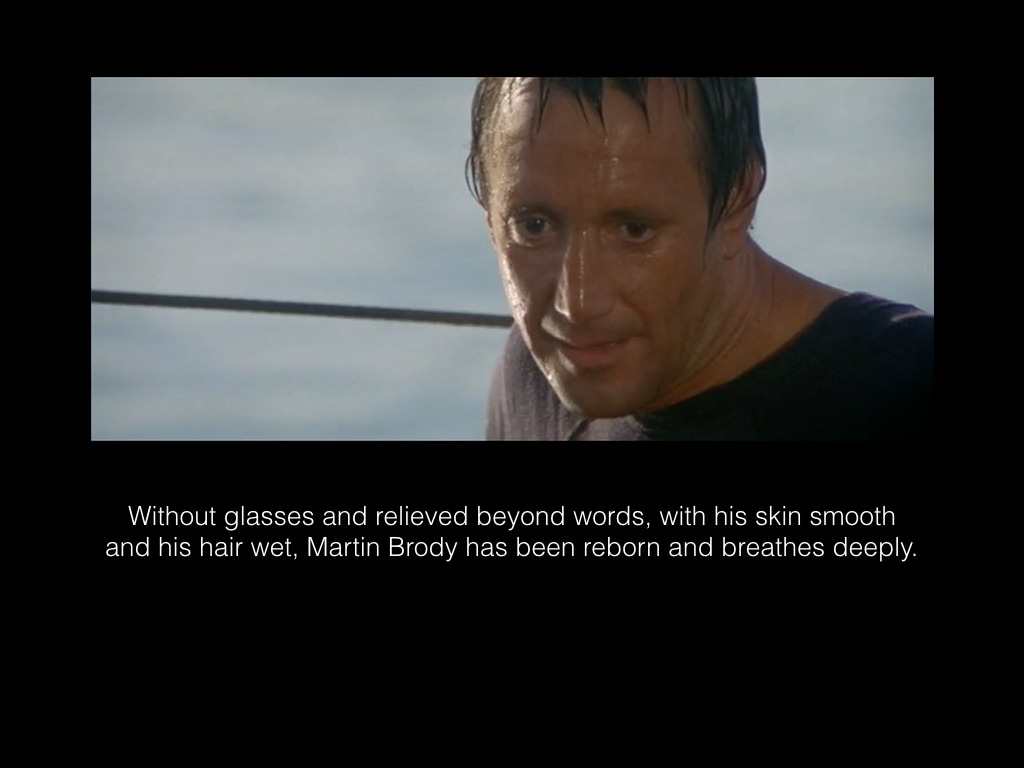

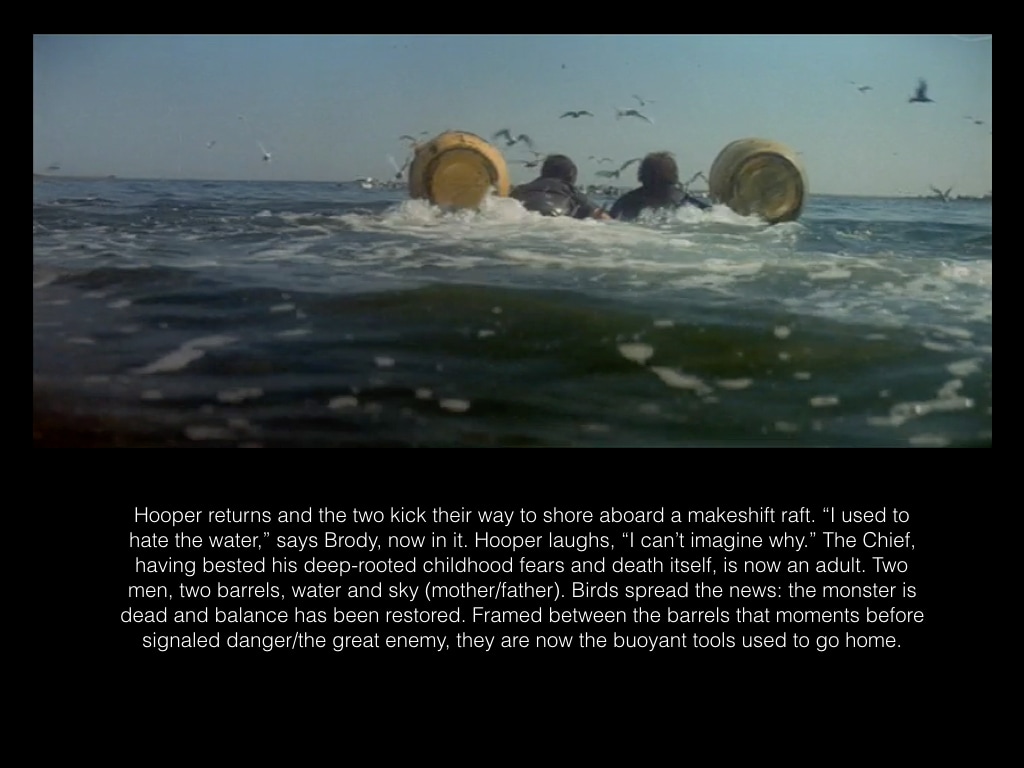

Four decades after its initial release, Jaws has more than withstood the test of time, having become a classic even in the eyes of many adults, critics, and cinéphiles. I hope that The Jaws Blog proves that this movie might even have something to say about its characters, particularly, its hero, Chief Brody—and that the problematic, mechanical shark is more than a hungry fish.… While I’m sure a few of the observations that follow are about aspects of the film that were not intentional on the part of Spielberg or his writers, I'd argue that Spielberg was often working through his sub-conscious, a powerful creative force. Film is a director’s medium, as they say—and what he decided to put on screen was not arbitrary, even if not debated for hours, even if spontaneous on that day to solve this or that problem. For the sub-conscious is often much more aware of what is going on, in the instant--particularly when an artist is firing on all cylinders.

Anyway, please except The Jaws Blog for what it is: an interpretation of a great film. Thanks for reading…

Note: Text copyright J. W Rinzler; Movie images copyright Universal Studios.

When I first saw Jaws back in 1975, I was only 12, but I knew that I’d experienced a movie unlike anything before. Jaws penetrated my inner psyche—not just because the shark was scary, but because the film was so fluid, so exciting to watch. I knew that whoever directed it should be tracked; his future films would be worth seeing, too.

I was one of the few who saw the uncut, more gruesome version of Jaws when it opened in Los Angeles. For years, I wasn’t sure if I was imagining things, but on subsequent viewings it always seemed like the scene in which Michael and his friends are attacked in the “pond” was shorter (I still seem remember more kids being killed, but that may be a trick of memory). Finally, various publications and DVD releases confirmed that the scene had been recut and toned down. (I'm pretty sure the autopsy scene was longer and more gruesome, too.) No matter. Its effect on me was long-lasting.

As it happened, I’d seen Sugarland Express, Spielberg’s previous feature film, by accident. Going forward, I never missed a Spielberg production. They were events. Even as his high-caliber output was unrivaled--Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Raiders of the Lost Ark—adults around me considered Jaws to be sensationalistic film fluff. After all, the story was pretty bare-bones: A shark eats several inhabitants of Amity, so a police chief has to rid the seas of the shark. But as a kid, I understood instinctively that it and Spielberg’s other films weren’t only about content—they were about the kinetic experience itself of film: the composition, editing, music, and all the things that go into a movie if you’re doing it right. To some extent, style is content. And Jaws was one hell of a style, an artistic achievement. Indeed, during those years, Spielberg was one of the most exuberant, inventive filmmakers in the history of cinema. Only Kubrick and Hitchcock come to mind as comparable Hollywood directors. Interestingly, Hitchcock’s later period segues into Spielberg and overlaps: Psycho (1960) and The Birds (1961) had prepared the terrain for Jaws. The last film directed by the Master of Suspense, Family Plot (1976), came out a year after Jaws.

Then Spielberg slowly but surely became more acceptable in the eyes of grown-ups and critics. The Color Purple had an ambivalent reception, as did Empire of the Sun, but Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan made him respectable worldwide.

Four decades after its initial release, Jaws has more than withstood the test of time, having become a classic even in the eyes of many adults, critics, and cinéphiles. I hope that The Jaws Blog proves that this movie might even have something to say about its characters, particularly, its hero, Chief Brody—and that the problematic, mechanical shark is more than a hungry fish.… While I’m sure a few of the observations that follow are about aspects of the film that were not intentional on the part of Spielberg or his writers, I'd argue that Spielberg was often working through his sub-conscious, a powerful creative force. Film is a director’s medium, as they say—and what he decided to put on screen was not arbitrary, even if not debated for hours, even if spontaneous on that day to solve this or that problem. For the sub-conscious is often much more aware of what is going on, in the instant--particularly when an artist is firing on all cylinders.

Anyway, please except The Jaws Blog for what it is: an interpretation of a great film. Thanks for reading…

Note: Text copyright J. W Rinzler; Movie images copyright Universal Studios.

If you want to leave a comment go to:

http://www.jwrinzler.com/comments/first-post#comments

http://www.jwrinzler.com/comments/first-post#comments