An Interview with Sequential Artist Legend—Will Eisner

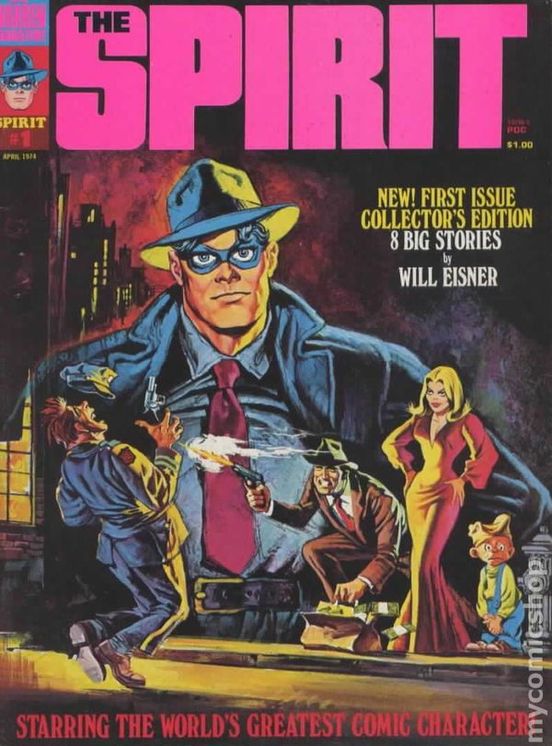

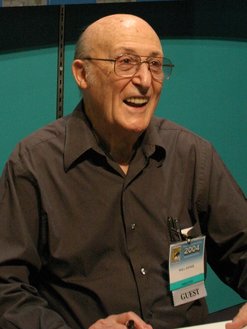

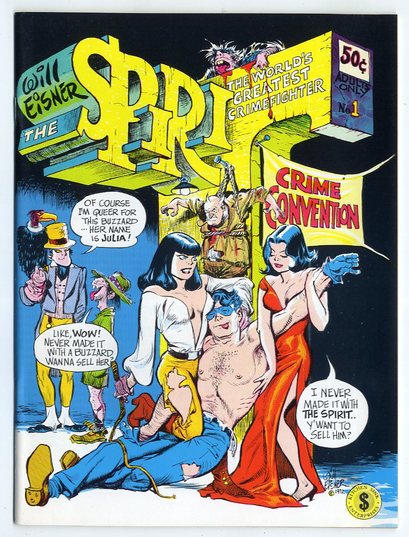

When I was about 12, I came upon the Warren magazine reprints of The Spirit by Will Eisner. This was about 1974. I found them at the store Comics and Comix, located on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, California, and the artwork and stories in these black-and-white magazines blew my mind. Decades later, I interviewed Will Eisner, on September 20, 2001. It was a lazy afternoon and we spoke on the phone for nearly two hours. The interview originally appeared on the GamePro magazine online site. But as that site has since disappeared, along with the magazine, I’ve dug up the interview. It should be read within the context of that time. A few years afterward, I met Will Eisner briefly while he was doing a signing at the San Diego Comic Con. He died on January 3, 2005.

So here’s the original intro, which is followed by the interview (annotated here and there for clarity’s sake).

Introduction

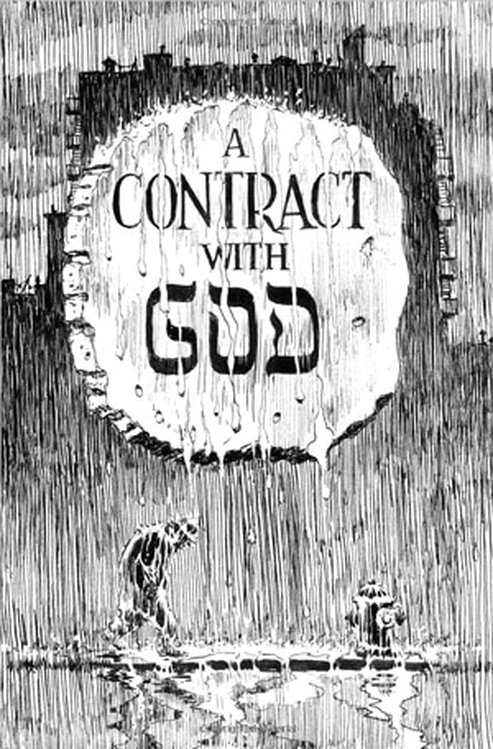

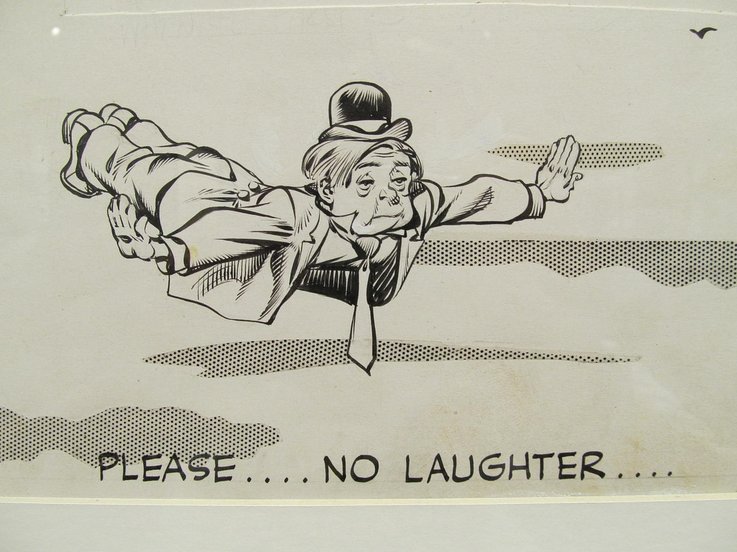

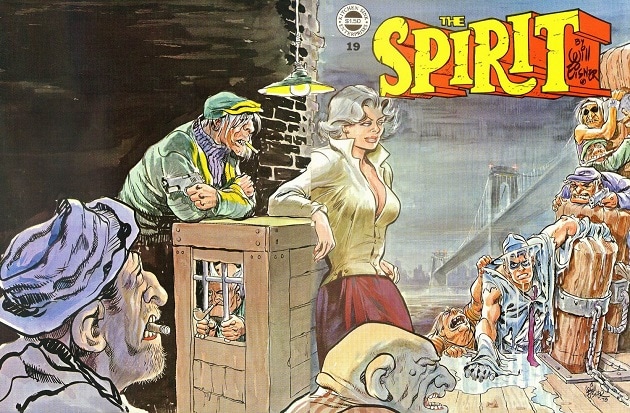

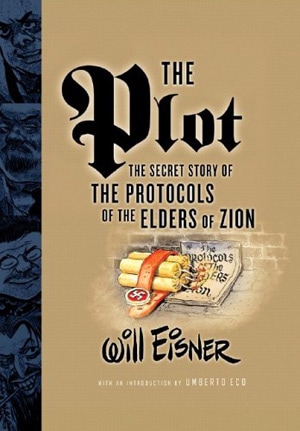

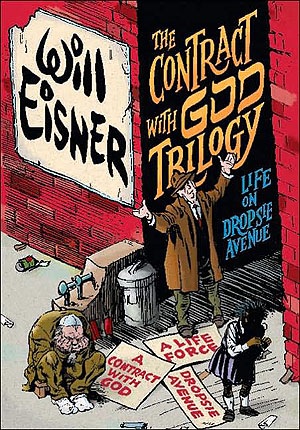

It’s not often that one gets a chance to talk to the heroes of one’s childhood. Last week, however, I had one of those rare moments when I interviewed Will Eisner. For the very young, Eisner’s name may mean little, but ask anyone who knows anything about comic books, and they know who he is: one of the Masters, along with Jack Kirby and a handful of others. His character The Spirit appeared in the 1940s and paved the way for hundreds of wannabes right up to Indiana Jones. Eisner has more recently published several graphic novels, notably A Contract with God (1978). Mr. Eisner is also an articulate spokesman for the comic book world, as he continues to demand its recognition as a legitimate art and literary form.

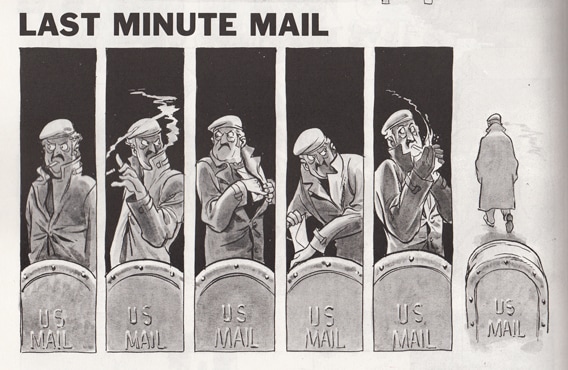

For me, though, Eisner will always be the author of dozens of tales that have no real equivalent. His skill, his “camera eye,” has no peer. In many ways, motion pictures and special-effects can’t match his fluid panels (still today). His writing elevates the ordinary to the spiritual; his brushwork is incredible. Some of these opening splash pages for The Spirit could be put in museums next to the works of Delacroix without suffering at all by comparison.

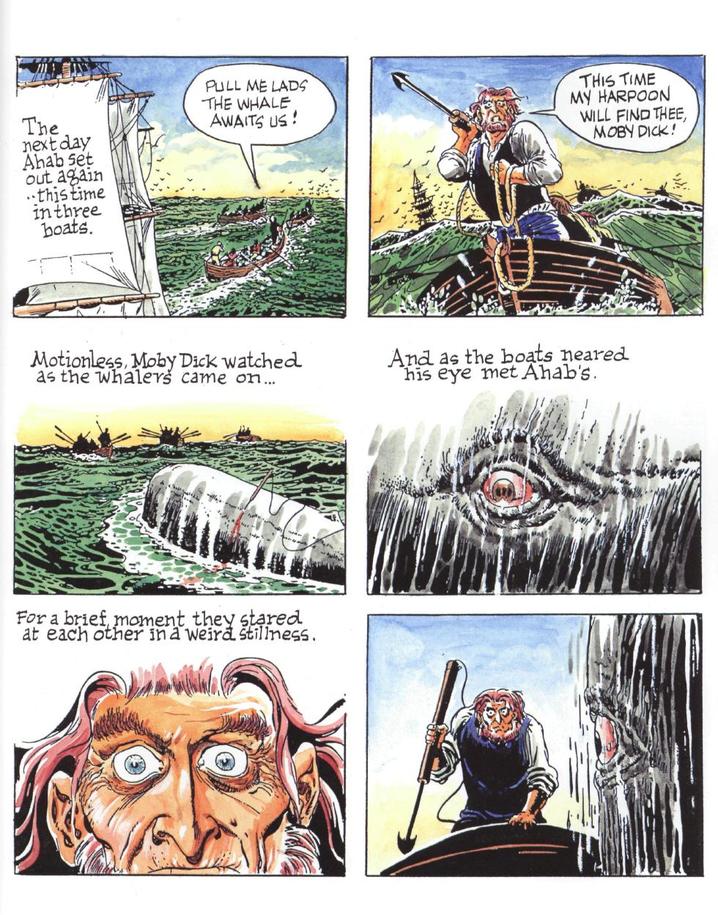

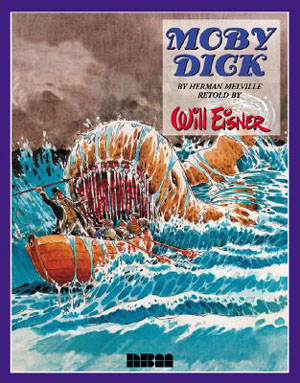

For all these reasons, it was a great pleasure to interview Mr. Eisner on the occasion of the publication of his adaptation of Herman Melville's Moby Dick. Hopefully, people who read this interview will be encouraged to go out and learn more about one of the legends of the comic book medium and one of the creators of the graphic novel.

(interview continued below....)

When I was about 12, I came upon the Warren magazine reprints of The Spirit by Will Eisner. This was about 1974. I found them at the store Comics and Comix, located on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley, California, and the artwork and stories in these black-and-white magazines blew my mind. Decades later, I interviewed Will Eisner, on September 20, 2001. It was a lazy afternoon and we spoke on the phone for nearly two hours. The interview originally appeared on the GamePro magazine online site. But as that site has since disappeared, along with the magazine, I’ve dug up the interview. It should be read within the context of that time. A few years afterward, I met Will Eisner briefly while he was doing a signing at the San Diego Comic Con. He died on January 3, 2005.

So here’s the original intro, which is followed by the interview (annotated here and there for clarity’s sake).

Introduction

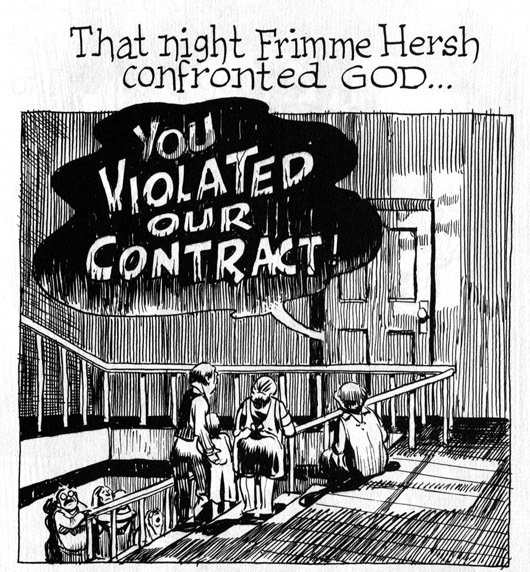

It’s not often that one gets a chance to talk to the heroes of one’s childhood. Last week, however, I had one of those rare moments when I interviewed Will Eisner. For the very young, Eisner’s name may mean little, but ask anyone who knows anything about comic books, and they know who he is: one of the Masters, along with Jack Kirby and a handful of others. His character The Spirit appeared in the 1940s and paved the way for hundreds of wannabes right up to Indiana Jones. Eisner has more recently published several graphic novels, notably A Contract with God (1978). Mr. Eisner is also an articulate spokesman for the comic book world, as he continues to demand its recognition as a legitimate art and literary form.

For me, though, Eisner will always be the author of dozens of tales that have no real equivalent. His skill, his “camera eye,” has no peer. In many ways, motion pictures and special-effects can’t match his fluid panels (still today). His writing elevates the ordinary to the spiritual; his brushwork is incredible. Some of these opening splash pages for The Spirit could be put in museums next to the works of Delacroix without suffering at all by comparison.

For all these reasons, it was a great pleasure to interview Mr. Eisner on the occasion of the publication of his adaptation of Herman Melville's Moby Dick. Hopefully, people who read this interview will be encouraged to go out and learn more about one of the legends of the comic book medium and one of the creators of the graphic novel.

(interview continued below....)

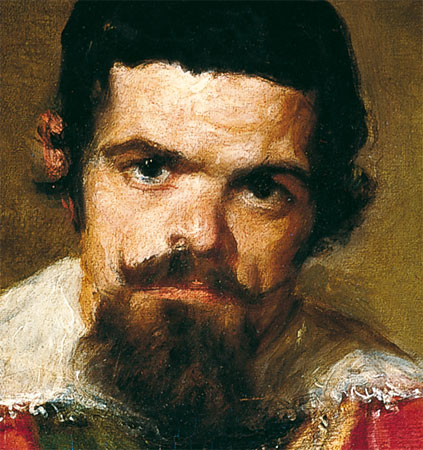

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Detail of Don Sebastián de Morra, ca. 1643–44, oil on canvas, 106 x 81 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid Photo © 2006 Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Detail of Don Sebastián de Morra, ca. 1643–44, oil on canvas, 106 x 81 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid Photo © 2006 Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

The Interview

J. W. Rinzler: Why did you first start drawing, as a kid?

Will Eisner: As a kid in the neighborhood I lived in, being a poor athlete was a very, very serious problem. But I could draw better than anybody else, so that was my claim to acceptance. Actually, it probably evolved from my father, who was an artist, a painter. I was also an avid reader, and I had a strong visual tendency, and so very early on I was drawing and writing and reading. When I grew up, I lucked out. Suddenly, there appeared a medium that involve both writing and drawing, so I could combine the two of them.

JWR: Why comic books instead of animation?

Eisner: Well, animation is a kind of process, a factory process. I wanted to be a painter originally and then I decided I wanted to be a writer, and I was interested in stage design and so forth. I was not a very good painter and I was not as good a writer as I should’ve been. These two ineptitudes put together made one ineptitude (laughs).

JWR: When did you first realize you could draw better than everybody else?

Eisner: In high school. My first comic book appeared in my high school newspaper. I was a big man in the art department there: I was the art director of the magazine, I wrote articles. The high school I went to was an all-boys school, a very competitive environment. I did wood engravings, I did a lot of things. Early in my high school, I was studying art at the Art Student’s League. I became aware of the Japanese woodcuts and I realized that that was storytelling. I was very attracted to anything that had a storytelling thrust. Back in elementary school, I was pretty good, too.

JWR: When you started drawing, who were your big inspirations?

Eisner: The great painters. Velasquez was always someone I admired. Turner, the impressionist, encouraged my feelings of legitimacy, because I realized later, through studying Turner, that cartoons were nothing more than informed Impressionism.

JWR: Did you admire the works of Goya?

Eisner: Goya, yes. Goya did some sequential art. There’s a great triptych that he did which was sequentially done. A lot of influences settled in on me. But Velasquez I liked because he was a master at internalizing characterizations. He was telling stories about life with his people.

JWR: So you weren’t just interested in those paintings per se. What interested you was art that told a story?

Eisner: That's right. That seemed to me to be more important than just style or technique. Velasquez's skill in rendering people—laughing people, the clerics—these are people that you really knew and understood. Later on, N. C. Wyeth and the great illustrators of that period became very influential. Remember the 1930s, the era that I grew up in, was very rich in illustrators. It was Dean Cornwell and others—they were terribly influential.

(Interview continued below....)

J. W. Rinzler: Why did you first start drawing, as a kid?

Will Eisner: As a kid in the neighborhood I lived in, being a poor athlete was a very, very serious problem. But I could draw better than anybody else, so that was my claim to acceptance. Actually, it probably evolved from my father, who was an artist, a painter. I was also an avid reader, and I had a strong visual tendency, and so very early on I was drawing and writing and reading. When I grew up, I lucked out. Suddenly, there appeared a medium that involve both writing and drawing, so I could combine the two of them.

JWR: Why comic books instead of animation?

Eisner: Well, animation is a kind of process, a factory process. I wanted to be a painter originally and then I decided I wanted to be a writer, and I was interested in stage design and so forth. I was not a very good painter and I was not as good a writer as I should’ve been. These two ineptitudes put together made one ineptitude (laughs).

JWR: When did you first realize you could draw better than everybody else?

Eisner: In high school. My first comic book appeared in my high school newspaper. I was a big man in the art department there: I was the art director of the magazine, I wrote articles. The high school I went to was an all-boys school, a very competitive environment. I did wood engravings, I did a lot of things. Early in my high school, I was studying art at the Art Student’s League. I became aware of the Japanese woodcuts and I realized that that was storytelling. I was very attracted to anything that had a storytelling thrust. Back in elementary school, I was pretty good, too.

JWR: When you started drawing, who were your big inspirations?

Eisner: The great painters. Velasquez was always someone I admired. Turner, the impressionist, encouraged my feelings of legitimacy, because I realized later, through studying Turner, that cartoons were nothing more than informed Impressionism.

JWR: Did you admire the works of Goya?

Eisner: Goya, yes. Goya did some sequential art. There’s a great triptych that he did which was sequentially done. A lot of influences settled in on me. But Velasquez I liked because he was a master at internalizing characterizations. He was telling stories about life with his people.

JWR: So you weren’t just interested in those paintings per se. What interested you was art that told a story?

Eisner: That's right. That seemed to me to be more important than just style or technique. Velasquez's skill in rendering people—laughing people, the clerics—these are people that you really knew and understood. Later on, N. C. Wyeth and the great illustrators of that period became very influential. Remember the 1930s, the era that I grew up in, was very rich in illustrators. It was Dean Cornwell and others—they were terribly influential.

(Interview continued below....)

Eisner at San Diego Comic-Con, 2004

Eisner at San Diego Comic-Con, 2004

JWR: Do you think you grew up at an opportune time?

Eisner: Oh, yes. No question about it. Fortunately, I arrived at the right moment. It was raining and I had a big bucket (laughs).

JWR: Do you think it’s harder today for kids to develop as artists and start a career?

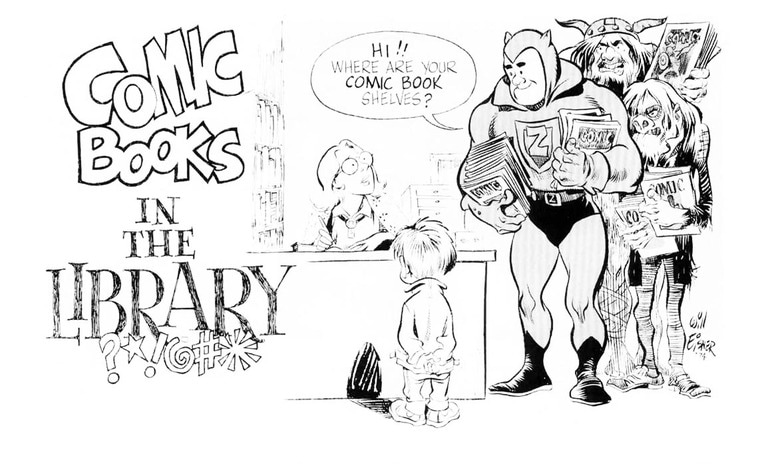

Eisner: Yes. I think it was a lot easier in my time because comics were a new burgeoning medium, an opportunity to be inventive. Anything we did was inventive. The big difference between today and then is that at that time, my peers were bringing into this medium things from the great classics. Whereas today, they’re regurgitating stuff that happened before. The kids today haven’t got the opportunity to bring into this medium things from somewhere else. The experiences that many young artists deal with today are very artificial, because they have little real experience. There are a few guys, however, working now that are beginning to touch on reality. Chris Ware, I hear, just did a story about a teenage girl who doesn't really know what she wants or where she is. I think that's good, that's very good.

Today comics as a medium have become well established. They're no longer a novelty. When I was starting it was new. It was evolving out of the daily strips and the pulps that were dying. But today, the marketplace is larger.

JWR: Do you think that an era’s big spurts of creativity stem from technical innovations? For example, comic strips were not just new, they took advantage of printing press innovations and a new method of telling stories?

Eisner: Well, that’s an interesting question. Technology is an important part of the creative process because technology is the vehicle of its transmission. But I don't believe that technology dominates content. What happens in the communication arts is that opportunities always present themselves, and the need to meet that opportunity creates inventiveness because you're trying to master the medium. As far as I was concerned, very early on, I saw comics as a growing literary art form. I knew that was going to be my life's work. Now a lot of the guys working in my studio at the time were working there to make some money, so they could go on to become illustrators and move uptown. Very few people early on saw this medium has a valid literary form.

JWR: Why do you think that you knew this would be your life work right from the get-go? Because it allowed you to draw and tell a story?

Eisner: I guess so. I guess so. You know it wasn't really an epiphany. It was a realization. It didn't take genius to see that this was an ongoing and valid medium. And it satisfied my needs. Because I love to write and I love to draw. Being an artist alone is not enough for me.

JWR: Would you mind going deeper and explaining why you love to draw? And why you love to write?

Eisner: I guess it's kind of like having an ability for music. I have a very strong visual memory. I have very good visual recall. And I love to tell stories. I guess by nature I'm a storyteller. And I guess I work on the left side of my brain, or is it the right side? (laughs)

JWR: I forget. The side that people rarely use…

Eisner: I see things in story form. I need to tell stories. It's the only way I can express myself. I guess that's the best way to answer your question. Each of us has a need to express himself. And each of us does it in his own way: the musician does it his way, the architect does it his way, and the mathematician does it his way... And I have opinions that need to be aired.

JWR: I've noticed that.

Eisner: (laughs) And I have to get rid of them. We all walk around with a demon inside of us that we have to exorcise once in a while. When I sit down and do a story I'm really writing a letter; my dialogue is very much in the language I'm using talking to you. I think of my reader while I'm writing. I write and draw at the same time; I don't use a typewriter. I don't see a separation between words and images. They are interconnected.

JWR: You don't go ahead and write your story first and then go back and draw it?

Eisnder: No. My general procedure is to write and draw at the same time in rough form. Then I'll go back and execute it on the drawing paper. The words and images are done almost at the same moment.

(Interview continued below....)

Eisner: Oh, yes. No question about it. Fortunately, I arrived at the right moment. It was raining and I had a big bucket (laughs).

JWR: Do you think it’s harder today for kids to develop as artists and start a career?

Eisner: Yes. I think it was a lot easier in my time because comics were a new burgeoning medium, an opportunity to be inventive. Anything we did was inventive. The big difference between today and then is that at that time, my peers were bringing into this medium things from the great classics. Whereas today, they’re regurgitating stuff that happened before. The kids today haven’t got the opportunity to bring into this medium things from somewhere else. The experiences that many young artists deal with today are very artificial, because they have little real experience. There are a few guys, however, working now that are beginning to touch on reality. Chris Ware, I hear, just did a story about a teenage girl who doesn't really know what she wants or where she is. I think that's good, that's very good.

Today comics as a medium have become well established. They're no longer a novelty. When I was starting it was new. It was evolving out of the daily strips and the pulps that were dying. But today, the marketplace is larger.

JWR: Do you think that an era’s big spurts of creativity stem from technical innovations? For example, comic strips were not just new, they took advantage of printing press innovations and a new method of telling stories?

Eisner: Well, that’s an interesting question. Technology is an important part of the creative process because technology is the vehicle of its transmission. But I don't believe that technology dominates content. What happens in the communication arts is that opportunities always present themselves, and the need to meet that opportunity creates inventiveness because you're trying to master the medium. As far as I was concerned, very early on, I saw comics as a growing literary art form. I knew that was going to be my life's work. Now a lot of the guys working in my studio at the time were working there to make some money, so they could go on to become illustrators and move uptown. Very few people early on saw this medium has a valid literary form.

JWR: Why do you think that you knew this would be your life work right from the get-go? Because it allowed you to draw and tell a story?

Eisner: I guess so. I guess so. You know it wasn't really an epiphany. It was a realization. It didn't take genius to see that this was an ongoing and valid medium. And it satisfied my needs. Because I love to write and I love to draw. Being an artist alone is not enough for me.

JWR: Would you mind going deeper and explaining why you love to draw? And why you love to write?

Eisner: I guess it's kind of like having an ability for music. I have a very strong visual memory. I have very good visual recall. And I love to tell stories. I guess by nature I'm a storyteller. And I guess I work on the left side of my brain, or is it the right side? (laughs)

JWR: I forget. The side that people rarely use…

Eisner: I see things in story form. I need to tell stories. It's the only way I can express myself. I guess that's the best way to answer your question. Each of us has a need to express himself. And each of us does it in his own way: the musician does it his way, the architect does it his way, and the mathematician does it his way... And I have opinions that need to be aired.

JWR: I've noticed that.

Eisner: (laughs) And I have to get rid of them. We all walk around with a demon inside of us that we have to exorcise once in a while. When I sit down and do a story I'm really writing a letter; my dialogue is very much in the language I'm using talking to you. I think of my reader while I'm writing. I write and draw at the same time; I don't use a typewriter. I don't see a separation between words and images. They are interconnected.

JWR: You don't go ahead and write your story first and then go back and draw it?

Eisnder: No. My general procedure is to write and draw at the same time in rough form. Then I'll go back and execute it on the drawing paper. The words and images are done almost at the same moment.

(Interview continued below....)

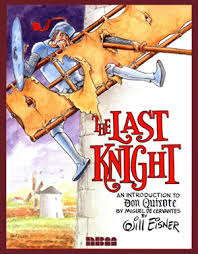

JWR: Speaking of your methodology, why did you decide to adapt stories for the NBM books instead of doing original stories as you usually do? [At the time Eisner had recently done a series of adaptations: Don Quixote, Moby Dick, and The Princess and the Frog.]

Eisner: Originally these books were part of a program that I developed for public television down here in Florida. They wanted to get into the literacy business, or anti-not-literacy (laughing). Illiteracy. We had a meeting and they asked me what I could propose. And I proposed something that would provide a reading experience on television that would elevate television in the eyes of the academics. And they thought that was a great idea and asked, “What stories will you do?”

And I said I thought the best thing to do would be to take classics and adapt them. Originally, the plan was to adapt them to little half-hour shows. They were still images with empty word balloons, and the words would pop into the balloons as they were spoken. I developed a whole series, about six of them, the first of which was Moby Dick. They spent a lot of money on it, but they were never able to get enough money to finish the series.

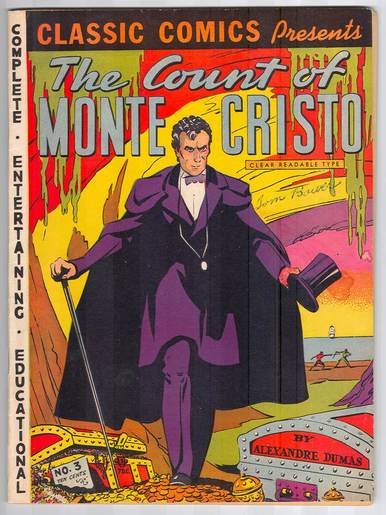

I had all the artwork lying around, so I began to organize it. But this wasn't the first time I did this type of adaptation. Back in 1937/38 when I had the Eisner/Iger studio, I created a series called Educational Comics, which later became Classic Comics. We adapted classics. The first one was The Count of Monte Cristo. As a matter of fact there was a fellow in my shop at the time who went by the name of Jacob Kurtzberg, who later became Jack Kirby—I don't know whatever happened to him… (laughs). And I assigned him a series of adaptations that we were selling to Europe at that time.

It's not a new idea at all. Actually these adaptations create another dimension that wasn't there originally. With Don Quixote what I did was create a scene where at the end Cervantes comes to visit Don Quixote and knights him. In a sense I’ve slightly rewritten it. I believe we’re all Don Quixotes anyway.

JWR: There's definitely a little bit of him in all of us. Is there a little bit of Captain Ahab in all of us, too?

Eisner: I was writing it from the point of view of the whale! The opening of the story is from the whale’s point of you. The whale is the hero of this thing.

JWR: So why Moby Dick in particular?

Eisner: I selected it because it had the potential for a great deal of motion. I should explain here that every time I finish a major graphic novel, I have a period of what could be called “post-partum depression” (laughs). And the only way to get myself out of it is to do something light and fun. The Princess and the Frog was kind of a fun thing to do.

JWR: The Princess and the Frog constantly bursts out of the frames, whereas Moby Dick is confined to its panels, why is that?

Eisner: It needed that. I don't think The Princess and the Frog would've read as well if it were confined to a series of panels. Moby Dick needed to be confined because it's almost as if it were kind of motion-dominated sequence.

JWR: In those panels I noticed that there are frequently large black areas, shadows, silhouettes, and so on…

Eisner: I do a lot of that. I think in terms of light and shadow. And this comes from growing up in the city. When you grow up in a city like New York, you're aware of a light that comes from a single direction. It comes from above or below. It doesn't come from the side. If you live in an open area like a farm, light comes from left and right.

JWR: That's interesting. I noticed in The Spirit that you made use of skylights frequently…

Eisner: Well, remember: When you grow up in concrete canyons, you think that way. The artists I know who grew up away from the cities invariably have a totally different view of light and shadow.

JWR: For a work like will Moby Dick, do you do much research to find out how to do the boats and clothing?

Eisner: Yeah, I do. I'm a lousy researcher. (laughs)

JWR: Do you have an assistant?

Eisner: Yeah, in that particular case, I had an assistant, Andre Leblanc, who just passed away. He’d been with me for years. He had been associated with me for 40 or 50 years. I generally use research material only for their information. I never use them to draw from. All I want to know is how many buttons are on the suit.

(Interview continued below....)

Eisner: Originally these books were part of a program that I developed for public television down here in Florida. They wanted to get into the literacy business, or anti-not-literacy (laughing). Illiteracy. We had a meeting and they asked me what I could propose. And I proposed something that would provide a reading experience on television that would elevate television in the eyes of the academics. And they thought that was a great idea and asked, “What stories will you do?”

And I said I thought the best thing to do would be to take classics and adapt them. Originally, the plan was to adapt them to little half-hour shows. They were still images with empty word balloons, and the words would pop into the balloons as they were spoken. I developed a whole series, about six of them, the first of which was Moby Dick. They spent a lot of money on it, but they were never able to get enough money to finish the series.

I had all the artwork lying around, so I began to organize it. But this wasn't the first time I did this type of adaptation. Back in 1937/38 when I had the Eisner/Iger studio, I created a series called Educational Comics, which later became Classic Comics. We adapted classics. The first one was The Count of Monte Cristo. As a matter of fact there was a fellow in my shop at the time who went by the name of Jacob Kurtzberg, who later became Jack Kirby—I don't know whatever happened to him… (laughs). And I assigned him a series of adaptations that we were selling to Europe at that time.

It's not a new idea at all. Actually these adaptations create another dimension that wasn't there originally. With Don Quixote what I did was create a scene where at the end Cervantes comes to visit Don Quixote and knights him. In a sense I’ve slightly rewritten it. I believe we’re all Don Quixotes anyway.

JWR: There's definitely a little bit of him in all of us. Is there a little bit of Captain Ahab in all of us, too?

Eisner: I was writing it from the point of view of the whale! The opening of the story is from the whale’s point of you. The whale is the hero of this thing.

JWR: So why Moby Dick in particular?

Eisner: I selected it because it had the potential for a great deal of motion. I should explain here that every time I finish a major graphic novel, I have a period of what could be called “post-partum depression” (laughs). And the only way to get myself out of it is to do something light and fun. The Princess and the Frog was kind of a fun thing to do.

JWR: The Princess and the Frog constantly bursts out of the frames, whereas Moby Dick is confined to its panels, why is that?

Eisner: It needed that. I don't think The Princess and the Frog would've read as well if it were confined to a series of panels. Moby Dick needed to be confined because it's almost as if it were kind of motion-dominated sequence.

JWR: In those panels I noticed that there are frequently large black areas, shadows, silhouettes, and so on…

Eisner: I do a lot of that. I think in terms of light and shadow. And this comes from growing up in the city. When you grow up in a city like New York, you're aware of a light that comes from a single direction. It comes from above or below. It doesn't come from the side. If you live in an open area like a farm, light comes from left and right.

JWR: That's interesting. I noticed in The Spirit that you made use of skylights frequently…

Eisner: Well, remember: When you grow up in concrete canyons, you think that way. The artists I know who grew up away from the cities invariably have a totally different view of light and shadow.

JWR: For a work like will Moby Dick, do you do much research to find out how to do the boats and clothing?

Eisner: Yeah, I do. I'm a lousy researcher. (laughs)

JWR: Do you have an assistant?

Eisner: Yeah, in that particular case, I had an assistant, Andre Leblanc, who just passed away. He’d been with me for years. He had been associated with me for 40 or 50 years. I generally use research material only for their information. I never use them to draw from. All I want to know is how many buttons are on the suit.

(Interview continued below....)

JWR: How did you go about adapting a 600-page-plus novel into a 40-plus page graphic novel?

Eisner: Well I went through it looking for the essentials of the story.

JWR: I notice that you included Fedella, who is almost always left out of adaptations. John Huston cut him out of his film adaptation, for example.

Eisner: I felt he belonged. I wasn't aware that Huston didn't put him in there. I was looking for dramatic elements, and he seemed to belong. Look, you know I have a lot of practice doing this. I spent a number of years turning out a complete story in seven pages every week. I had to learn how to do that very early on. In fact I learned from reading pulps, the short stories of the 1930s is something I paid a lot of attention to. O. Henry was a master of that.

JWR: What kind of material do you use?

Eisner: I generally work with a Windsor-Newton Kolinski sable-hair number two or number three brush. I use black ink and then I watercolor on top of it. I use a pen for hard surfaces, like walls and windows and stuff like that, and I use a brush for people.

JWR: You have an amazing facility with the brush.

Eisner: It's a matter of practice I guess. Using a brush is kind of like skating downhill. It's very sensual for me. I love working with the brush.

JWR: I have to admit that because I read your comics first when I was growing up, that when I saw Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo’s drawings, I thought, These guys are drawing like Will Eisner! (laughs)

Eisner: I've always suspected them of swiping from me… (laughs)

JWR: Your lines have always seemed incredibly expressive to me. Did you continue to study how Japanese artists painted?

Eisner: Early Japanese woodcuts, like Hiroshigi woodcuts. Actually the artist would draw on the wood with a brush, and the wood would be carved by his assistants. As a matter of fact I used a Japanese brush in the early Spirit stories. It’s only later that I stopped, because Japanese brushes have a tendency to not snap back. The hair they use is usually dog hair or rabbit hair or so forth. The Windsor-Newtons are sable, and sable has a resilience, a greater response. They enable you to work faster.

(Interview continued below....)

Eisner: Well I went through it looking for the essentials of the story.

JWR: I notice that you included Fedella, who is almost always left out of adaptations. John Huston cut him out of his film adaptation, for example.

Eisner: I felt he belonged. I wasn't aware that Huston didn't put him in there. I was looking for dramatic elements, and he seemed to belong. Look, you know I have a lot of practice doing this. I spent a number of years turning out a complete story in seven pages every week. I had to learn how to do that very early on. In fact I learned from reading pulps, the short stories of the 1930s is something I paid a lot of attention to. O. Henry was a master of that.

JWR: What kind of material do you use?

Eisner: I generally work with a Windsor-Newton Kolinski sable-hair number two or number three brush. I use black ink and then I watercolor on top of it. I use a pen for hard surfaces, like walls and windows and stuff like that, and I use a brush for people.

JWR: You have an amazing facility with the brush.

Eisner: It's a matter of practice I guess. Using a brush is kind of like skating downhill. It's very sensual for me. I love working with the brush.

JWR: I have to admit that because I read your comics first when I was growing up, that when I saw Leonardo Da Vinci and Michelangelo’s drawings, I thought, These guys are drawing like Will Eisner! (laughs)

Eisner: I've always suspected them of swiping from me… (laughs)

JWR: Your lines have always seemed incredibly expressive to me. Did you continue to study how Japanese artists painted?

Eisner: Early Japanese woodcuts, like Hiroshigi woodcuts. Actually the artist would draw on the wood with a brush, and the wood would be carved by his assistants. As a matter of fact I used a Japanese brush in the early Spirit stories. It’s only later that I stopped, because Japanese brushes have a tendency to not snap back. The hair they use is usually dog hair or rabbit hair or so forth. The Windsor-Newtons are sable, and sable has a resilience, a greater response. They enable you to work faster.

(Interview continued below....)

Jack Kirby and Status

JWR: You spoke of Jack Kirby before. What was it like working with him?

Eisner: Well it was a short, but very satisfactory relationship. He was working with me for a while in my shop, along with all the other guys, and we knew each other fairly well, but we were not social. He left after a little more than a year and I lost touch with him. I didn't see him until years later when we started to meet at conventions, and he used to call me "boss." Actually our relationship at the time was more of a shop relationship, because his attitude was not "intellectual" in the way Jules Feiffer’s was when he worked with me. In the case of Kirby, he thought of it as a job; to him, it was like doing piecework at a shirt factory. We never spent any time discussing the work intellectually.

JWR: I recently re-read your interview with Kirby in Shop Talk (a book of reprints of interviews Eisner did with comic book artists)--

Eisner: It was a very difficult one, by the way.

JWR: I could tell.

Eisner: I couldn't get him to go beyond the platitudes he’d learned all these years.

JWR: Why do you think he was reticent?

Eisner: It simply wasn't there. Jack's attitude toward this business, this medium, was different than mine. To me, it's more of a literary form. I could hold a conversation with Milton Caniff; I could go into it a little more deeply and talk about the literary aspects of the medium. But Kirby gave me a hard time with that interview because he said he didn't really think he was doing anything literary. He was being a cartoonist; the craft and character’s novelty was his major interest.

JWR: Do you think that might be because if artists admit that they think they're doing something literary that they feel they're setting themselves up to be knocked down?

Eisner: Well, yeah. Remember also, there’s what I call a “slave mentality.” If you've been working for years in the comic book industry, you were told that you were only producing hamburgers. There's a German word for it: We were üntermenschen. You know what I mean. After a while, you get to believe it. I know when I did an interview with the Baltimore Sun in 1940 just after The Spirit started, I said that I thought this was a literary art form. When I came back to New York all the guys laughed at me, and said, "You're being uppity, Will."

JWR: At the outset of the Renaissance, painters were paid less, I believe, than shoemakers.

Eisner: It's true. We are still regarded by the intellectual elite in this country as working in what I call a "despised" medium. Really, why should oil painting be considered a "fine" art. Why? We have a hierarchy here. Why should comic books be way, way down at the bottom—just above graffiti. Why should etching be more important in the scheme of things? Why should Picasso, who was a cartoonist as far as I'm concerned, be regarded as a great, great artist?

JWR: It does seem arbitrary.

Eisner: You get a guy like Warhol drawing cans. I had a meeting with a museum director here [Boca Raton] and I tried to convince him that he should have an art show of cartoonists—I said, “You've already been showing cartoonists.” And he said, “Who?” And I said, “Picasso.” And his eyes glazed over and he looked at his watch, and suddenly he had to go to an appointment.

JWR: That's pretty rigid.

Eisner: Well, we have a society in which self-appointed critics ordain what is good and what isn't.

JWR: Are you skeptical of Abstract Expressionism’s real contribution to art?

Eisner: No, I can't be skeptical, because any creative effort has an effect on our standards and our tastes. For example Mondrian, with his very geometric abstractions, had a strong influence on the architecture of our buildings. The thing I object to is that our culture ordains certain things as being better than others. And it makes it more difficult for a medium like ours to rise to the level that would make it more worthwhile. The Cartoon Museum in Florida is floundering. We're having terrible economic problems. We may have to close. Unless museums have a huge endowment they can't survive. They can't live off the "gate" so to speak.

JWR: How come the museum can't get an endowment?

Eisner: In a city like Boca Raton, there are many very, very wealthy people, but how can these people go to the country club on Saturday night and say, “I’ve just given $100,000 to a cartoon museum”? They could give that money to the fine arts museum uptown. They're buying status, community status. It has not been able to secure the community financial support the “fine arts” museum has enjoyed. [Note: The International Museum of Cartoon Art closed its doors for good in 2002.]

(Interview continued below....)

JWR: You spoke of Jack Kirby before. What was it like working with him?

Eisner: Well it was a short, but very satisfactory relationship. He was working with me for a while in my shop, along with all the other guys, and we knew each other fairly well, but we were not social. He left after a little more than a year and I lost touch with him. I didn't see him until years later when we started to meet at conventions, and he used to call me "boss." Actually our relationship at the time was more of a shop relationship, because his attitude was not "intellectual" in the way Jules Feiffer’s was when he worked with me. In the case of Kirby, he thought of it as a job; to him, it was like doing piecework at a shirt factory. We never spent any time discussing the work intellectually.

JWR: I recently re-read your interview with Kirby in Shop Talk (a book of reprints of interviews Eisner did with comic book artists)--

Eisner: It was a very difficult one, by the way.

JWR: I could tell.

Eisner: I couldn't get him to go beyond the platitudes he’d learned all these years.

JWR: Why do you think he was reticent?

Eisner: It simply wasn't there. Jack's attitude toward this business, this medium, was different than mine. To me, it's more of a literary form. I could hold a conversation with Milton Caniff; I could go into it a little more deeply and talk about the literary aspects of the medium. But Kirby gave me a hard time with that interview because he said he didn't really think he was doing anything literary. He was being a cartoonist; the craft and character’s novelty was his major interest.

JWR: Do you think that might be because if artists admit that they think they're doing something literary that they feel they're setting themselves up to be knocked down?

Eisner: Well, yeah. Remember also, there’s what I call a “slave mentality.” If you've been working for years in the comic book industry, you were told that you were only producing hamburgers. There's a German word for it: We were üntermenschen. You know what I mean. After a while, you get to believe it. I know when I did an interview with the Baltimore Sun in 1940 just after The Spirit started, I said that I thought this was a literary art form. When I came back to New York all the guys laughed at me, and said, "You're being uppity, Will."

JWR: At the outset of the Renaissance, painters were paid less, I believe, than shoemakers.

Eisner: It's true. We are still regarded by the intellectual elite in this country as working in what I call a "despised" medium. Really, why should oil painting be considered a "fine" art. Why? We have a hierarchy here. Why should comic books be way, way down at the bottom—just above graffiti. Why should etching be more important in the scheme of things? Why should Picasso, who was a cartoonist as far as I'm concerned, be regarded as a great, great artist?

JWR: It does seem arbitrary.

Eisner: You get a guy like Warhol drawing cans. I had a meeting with a museum director here [Boca Raton] and I tried to convince him that he should have an art show of cartoonists—I said, “You've already been showing cartoonists.” And he said, “Who?” And I said, “Picasso.” And his eyes glazed over and he looked at his watch, and suddenly he had to go to an appointment.

JWR: That's pretty rigid.

Eisner: Well, we have a society in which self-appointed critics ordain what is good and what isn't.

JWR: Are you skeptical of Abstract Expressionism’s real contribution to art?

Eisner: No, I can't be skeptical, because any creative effort has an effect on our standards and our tastes. For example Mondrian, with his very geometric abstractions, had a strong influence on the architecture of our buildings. The thing I object to is that our culture ordains certain things as being better than others. And it makes it more difficult for a medium like ours to rise to the level that would make it more worthwhile. The Cartoon Museum in Florida is floundering. We're having terrible economic problems. We may have to close. Unless museums have a huge endowment they can't survive. They can't live off the "gate" so to speak.

JWR: How come the museum can't get an endowment?

Eisner: In a city like Boca Raton, there are many very, very wealthy people, but how can these people go to the country club on Saturday night and say, “I’ve just given $100,000 to a cartoon museum”? They could give that money to the fine arts museum uptown. They're buying status, community status. It has not been able to secure the community financial support the “fine arts” museum has enjoyed. [Note: The International Museum of Cartoon Art closed its doors for good in 2002.]

(Interview continued below....)

Return of The Spirit

JWR: How do you feel about The Spirit now, on a personal level?

Eisner: I still like the character. I enjoyed doing him, and I was very pleased at what I did with him. I still think of him kindly. I don't think I have any interest in doing new Spirit stories, if that's what you're leading up to?

JWR: Is there any possibility of doing a Spirit movie?

Eisner: I licensed a group to do a movie about six years ago. The film was done by Warner Bros., a one hour TV film, about 1985, but it never went anywhere. I really have no interest in the Spirit movie.

JWR: From your writings and so on, it doesn't seem like you're very interested in storytelling through the medium of film. Is that true?

Eisner: I watch movies. I love to watch movies. I don't feel that I would like to tell my stories in that medium though. Making a movie is a cooperative venture. It involves many people, and that dilutes it for me. I prefer to be everything: I'm the actor, the director… I have total control, so it gives me the kind of satisfaction I want. Even if I were invited to do storyboards for movie, the result wouldn't be mine.

JWR: Would you consider matte paintings for films an art form?

Eisner: I think that's more to do with technique, but it's what they do with it, what's in it, that counts. Sure, it's an art form. Anything that a human being does creatively is an art form. Animation can be an artform depending on what you do with it—that's the important thing. Fantasia and the things that Disney did were a great use of the art form.

JWR: What do you think of the more recent Disney films Aladdin and The little Mermaid?

Eisner: I wasn't too intrigued with those. I didn't think they were as inventive or groundbreaking as the early ones.

JWR: What do you think of the storytelling capabilities of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas?

Eisner: Spielberg is a master storyteller. I think he's a great director. Actually I don't really know how much a director is responsible for what happens in the movie. There's camera work, there’s splendid acting… They contribute to the final product. I don't know, maybe the director is like an editor.

JWR: So you're not sold on the auteur theory?

Eisner: No, I don't think of them as auteurs. George Lucas has apparently engineered these things so beautifully, but, again, I don't know how much credit he should get. There must be some special effects guys who knows how to make things fly and that sort of thing. I really don't know much about the process of movie-making.

JWR: Speaking of special effects, do you think that computer graphics are going to take away anything from comic books? We're seeing more and more comic-book adaptations as films are able to imitate more easily what used to be the exclusive domain of comics…

Eisner: No, no. The single frame that we do is good only for print. What it does is serve a method of transmission to a marketplace. Comic book artists often say, "Well, I'm going to do something that has movie possibilities." But they’re not creating something for film. They are writing for print readers. The movie business looks on comics as a mine, as a source for creative ideas. And that's how it should be, because the comic book artist is really a creative force. Movies simply adapt. It's a machinery, as far as I can see. They don't create anything. They don't generate an idea for a product. They influence young cartoonists because they appear to be a market.

JWR: So you're not afraid that the simple panel on the page is at all in jeopardy?

Eisner: No. Print will remain for a long, long time. Print has properties that electronic transmission cannot provide you with. You don't have time with electronic transmissions to dwell on something. It's going too fast. I don't think print is going to dominate our society the way it did, however.

JWR: I had to ask that question…

Eisner: I expected it sooner or later (laughs).

(Interview continued below....)

JWR: How do you feel about The Spirit now, on a personal level?

Eisner: I still like the character. I enjoyed doing him, and I was very pleased at what I did with him. I still think of him kindly. I don't think I have any interest in doing new Spirit stories, if that's what you're leading up to?

JWR: Is there any possibility of doing a Spirit movie?

Eisner: I licensed a group to do a movie about six years ago. The film was done by Warner Bros., a one hour TV film, about 1985, but it never went anywhere. I really have no interest in the Spirit movie.

JWR: From your writings and so on, it doesn't seem like you're very interested in storytelling through the medium of film. Is that true?

Eisner: I watch movies. I love to watch movies. I don't feel that I would like to tell my stories in that medium though. Making a movie is a cooperative venture. It involves many people, and that dilutes it for me. I prefer to be everything: I'm the actor, the director… I have total control, so it gives me the kind of satisfaction I want. Even if I were invited to do storyboards for movie, the result wouldn't be mine.

JWR: Would you consider matte paintings for films an art form?

Eisner: I think that's more to do with technique, but it's what they do with it, what's in it, that counts. Sure, it's an art form. Anything that a human being does creatively is an art form. Animation can be an artform depending on what you do with it—that's the important thing. Fantasia and the things that Disney did were a great use of the art form.

JWR: What do you think of the more recent Disney films Aladdin and The little Mermaid?

Eisner: I wasn't too intrigued with those. I didn't think they were as inventive or groundbreaking as the early ones.

JWR: What do you think of the storytelling capabilities of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas?

Eisner: Spielberg is a master storyteller. I think he's a great director. Actually I don't really know how much a director is responsible for what happens in the movie. There's camera work, there’s splendid acting… They contribute to the final product. I don't know, maybe the director is like an editor.

JWR: So you're not sold on the auteur theory?

Eisner: No, I don't think of them as auteurs. George Lucas has apparently engineered these things so beautifully, but, again, I don't know how much credit he should get. There must be some special effects guys who knows how to make things fly and that sort of thing. I really don't know much about the process of movie-making.

JWR: Speaking of special effects, do you think that computer graphics are going to take away anything from comic books? We're seeing more and more comic-book adaptations as films are able to imitate more easily what used to be the exclusive domain of comics…

Eisner: No, no. The single frame that we do is good only for print. What it does is serve a method of transmission to a marketplace. Comic book artists often say, "Well, I'm going to do something that has movie possibilities." But they’re not creating something for film. They are writing for print readers. The movie business looks on comics as a mine, as a source for creative ideas. And that's how it should be, because the comic book artist is really a creative force. Movies simply adapt. It's a machinery, as far as I can see. They don't create anything. They don't generate an idea for a product. They influence young cartoonists because they appear to be a market.

JWR: So you're not afraid that the simple panel on the page is at all in jeopardy?

Eisner: No. Print will remain for a long, long time. Print has properties that electronic transmission cannot provide you with. You don't have time with electronic transmissions to dwell on something. It's going too fast. I don't think print is going to dominate our society the way it did, however.

JWR: I had to ask that question…

Eisner: I expected it sooner or later (laughs).

(Interview continued below....)

On Life and Death

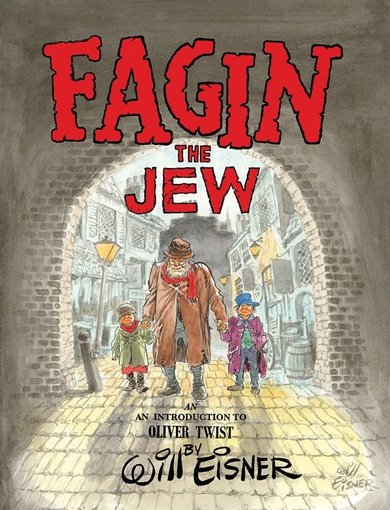

JWR: You've talked about how growing up in New York City had an influence on your art. Would you say that being Jewish has had an effect on you?

Eisner: Oh, yes. Jewish culture is very story oriented. Jews over the centuries have passed down a kind of cultural gene, if you will, which is centered on the question of life and living. You hear stories all your life. My concern has always been with man's struggle with life. Life is the enemy, as far as I’m concerned. The Bible is all stories.

JWR: That's funny, because I've always found your work somehow optimistic.

Eisner: I'm an optimist because I keep hoping that man can prevail. I wouldn't point out to you a social horror unless I thought there was some hope that by you and someone else seeing it, something could be done about correcting it. But I'm not a moralist. What I do is reportage.

JWR: But "life is the enemy" is pretty strong. Could you explain that a bit more?

Eisner: We struggle to stay alive; survival is the very essence of our activity. We spend all day in the process of surviving against an implacable force, which is, ultimately, death.

JWR: Is death the final word for you?

Eisner: I would like to believe that it is not, frankly. But so far I haven't seen any evidence to the contrary. I'd like to believe in a higher intelligence, but so far it seems to me that in the contract that we have with God, neither party has lived up to their obligations.

(Interview continued below....)

JWR: You've talked about how growing up in New York City had an influence on your art. Would you say that being Jewish has had an effect on you?

Eisner: Oh, yes. Jewish culture is very story oriented. Jews over the centuries have passed down a kind of cultural gene, if you will, which is centered on the question of life and living. You hear stories all your life. My concern has always been with man's struggle with life. Life is the enemy, as far as I’m concerned. The Bible is all stories.

JWR: That's funny, because I've always found your work somehow optimistic.

Eisner: I'm an optimist because I keep hoping that man can prevail. I wouldn't point out to you a social horror unless I thought there was some hope that by you and someone else seeing it, something could be done about correcting it. But I'm not a moralist. What I do is reportage.

JWR: But "life is the enemy" is pretty strong. Could you explain that a bit more?

Eisner: We struggle to stay alive; survival is the very essence of our activity. We spend all day in the process of surviving against an implacable force, which is, ultimately, death.

JWR: Is death the final word for you?

Eisner: I would like to believe that it is not, frankly. But so far I haven't seen any evidence to the contrary. I'd like to believe in a higher intelligence, but so far it seems to me that in the contract that we have with God, neither party has lived up to their obligations.

(Interview continued below....)

Secrets of Sequential Art

JWR: You’ve written a couple books about how to create comic books. Could you filter that down to one or two essentials?

Eisner: For someone who draws comic books, the first thing to do is to learn how to manipulate the human machine. So begin by imitating. I used to have big arguments with other teachers who said I shouldn't say that. But I don't believe that. I believe that people ultimately come out of imitation to develop their own style and personality.

JWR: To bring up the Renaissance again, during those times, the feeling was that artistic talent wasn't considered a prerequisite for being an artist. Do you think that just by teaching the basics, that a systematic approach can create artists?

Eisner: Well, those were technicians; that was what the Renaissance was turning out to some degree. Cartoons are generally done by people who have something to say. The way to have something to say is to keep yourself informed. Learn the basic mechanics needed to create images. When I see kids copying Mickey Mouse, I say fine—up to a point.

JWR: You mentioned Picasso before, and he once said that the important part of creation is the process not the finished product. Do you agree with that?

Eisner: I have doubts about that. I disagree with him. It's like the painter who says he paints to satisfy himself. Yes, you enjoy the medium because you enjoy working in the medium; it satisfies something within you. But the medium is used to say something. It's like writing. If you're working in comics, a communication art, then you have to have something to say.

JWR: But while you're creating, don't you find out things about yourself?

Eisner: Perhaps. But mostly you discover the limits of your ability. I’ve discovered things in myself over the years through the stories I wanted to tell; I've unburdened myself, perhaps. I've never really had any problem discovering myself. When students used to come to me and say, "I'm trying to find myself,” I couldn't connect with that. I've struggled with my feeling of inadequacy, which is something you work on constantly.

JWR: Well, as far as I'm concerned some of the opening pages of The Spirit comics are among the most poetic things ever committed to paper, if that helps.

Eisner: Well, I love to hear it. Those were hard days for me. I was reaching out, standing on my toes, saying, “Pay attention to me."

JWR: And much of the stuff in Moby Dick, like where the whale and Ahab stare at each other, is really fine.

Eisner: Well, thank you.

JWR: Was there any specific inspiration for those rain-soaked Spirit openings?

Eisner: No. They were the result of an effort to reach people within the limits of this medium; I'm trying constantly to make a connection with the reader, to evoke emotion. The only thing I envy in the movies is that they can make people cry. I wanted to use a device that would bring in people emotionally. Everyone knows what rain feels like; everyone knows what heat feels like. Those are the only tools I had available.

JWR: You wanted a visceral response.

Eisner: Exactly. Everything I do is prefaced by the words, “Believe me.”

JWR: Are you working on anything right now that you can talk about?

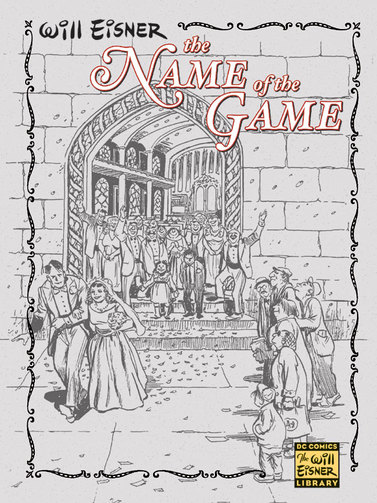

Eisner: Yeah I just finished a book called The Name of the Game, which DC is going to publish this fall. It's a big book, about 168 pages. It has to do with the dynamics of marriage.

JWR: Once again you've targeted a problem and now you're reporting it? (laughs)

Eisner: Well I was doing the research for The Princess and the Frog, I was going through all the fairytales, the Grimm stories, and the Jewish folk tales, and I discovered something very interesting: Throughout all the stories, there turned out to be one major way that people elevated themselves out of poverty—and that is by marrying the king’s daughter. It struck me that it seems to have been going on for a long time.

JWR: That's the joke: "Don't marry for money. Go where the rich people are and fall in love."

Eisner: I never heard that one (laughs). So the book dramatizes one such situation. I start off with a small idea and it constantly gets larger and larger. Anyway, I just finished that, so I'm looking at fairytales again because I want to decompress.

(Interview continued below....)

JWR: You’ve written a couple books about how to create comic books. Could you filter that down to one or two essentials?

Eisner: For someone who draws comic books, the first thing to do is to learn how to manipulate the human machine. So begin by imitating. I used to have big arguments with other teachers who said I shouldn't say that. But I don't believe that. I believe that people ultimately come out of imitation to develop their own style and personality.

JWR: To bring up the Renaissance again, during those times, the feeling was that artistic talent wasn't considered a prerequisite for being an artist. Do you think that just by teaching the basics, that a systematic approach can create artists?

Eisner: Well, those were technicians; that was what the Renaissance was turning out to some degree. Cartoons are generally done by people who have something to say. The way to have something to say is to keep yourself informed. Learn the basic mechanics needed to create images. When I see kids copying Mickey Mouse, I say fine—up to a point.

JWR: You mentioned Picasso before, and he once said that the important part of creation is the process not the finished product. Do you agree with that?

Eisner: I have doubts about that. I disagree with him. It's like the painter who says he paints to satisfy himself. Yes, you enjoy the medium because you enjoy working in the medium; it satisfies something within you. But the medium is used to say something. It's like writing. If you're working in comics, a communication art, then you have to have something to say.

JWR: But while you're creating, don't you find out things about yourself?

Eisner: Perhaps. But mostly you discover the limits of your ability. I’ve discovered things in myself over the years through the stories I wanted to tell; I've unburdened myself, perhaps. I've never really had any problem discovering myself. When students used to come to me and say, "I'm trying to find myself,” I couldn't connect with that. I've struggled with my feeling of inadequacy, which is something you work on constantly.

JWR: Well, as far as I'm concerned some of the opening pages of The Spirit comics are among the most poetic things ever committed to paper, if that helps.

Eisner: Well, I love to hear it. Those were hard days for me. I was reaching out, standing on my toes, saying, “Pay attention to me."

JWR: And much of the stuff in Moby Dick, like where the whale and Ahab stare at each other, is really fine.

Eisner: Well, thank you.

JWR: Was there any specific inspiration for those rain-soaked Spirit openings?

Eisner: No. They were the result of an effort to reach people within the limits of this medium; I'm trying constantly to make a connection with the reader, to evoke emotion. The only thing I envy in the movies is that they can make people cry. I wanted to use a device that would bring in people emotionally. Everyone knows what rain feels like; everyone knows what heat feels like. Those are the only tools I had available.

JWR: You wanted a visceral response.

Eisner: Exactly. Everything I do is prefaced by the words, “Believe me.”

JWR: Are you working on anything right now that you can talk about?

Eisner: Yeah I just finished a book called The Name of the Game, which DC is going to publish this fall. It's a big book, about 168 pages. It has to do with the dynamics of marriage.

JWR: Once again you've targeted a problem and now you're reporting it? (laughs)

Eisner: Well I was doing the research for The Princess and the Frog, I was going through all the fairytales, the Grimm stories, and the Jewish folk tales, and I discovered something very interesting: Throughout all the stories, there turned out to be one major way that people elevated themselves out of poverty—and that is by marrying the king’s daughter. It struck me that it seems to have been going on for a long time.

JWR: That's the joke: "Don't marry for money. Go where the rich people are and fall in love."

Eisner: I never heard that one (laughs). So the book dramatizes one such situation. I start off with a small idea and it constantly gets larger and larger. Anyway, I just finished that, so I'm looking at fairytales again because I want to decompress.

(Interview continued below....)

Final Words

JWR: In the 1950s the authorities attacked comics as being too violent. Today, video games are being attacked in the same way. What do you think about that?

Eisner: I think about it the same way I thought about it then: It's nonsense. Video games are an outlet for kids. Yes, it would seem we’re living in a more violent society now. But we used to come out of cowboy movies running around the street shooting each other in the "good ol’ days.” I don't think we should close down video games; I don't think we should edit them. I think they should go their course.

JWR: Is there anything that you'd like to saying closing?

Eisner: I enjoyed doing Moby Dick. It was fun.

JWR: So after all this time, you're still enjoying it?

Eisner: Oh, yes. I don't believe in retirement. Retirement is for people who are lying in their graves.

JWR: Or for people who don't like their jobs…

Eisner: Well, they shouldn't retire. They should quit and do something else. I'm still trying to get the brass ring; I still want to produce the work that's perfect.

JWR Leonardo da Vinci said that the great artist was the one who is never satisfied with his work.

Eisner: That's true. And since were quoting people (laughs), Rembrandt’s dying words were, "There's so much yet to do."

JWR: If it's any consolation, as a less critical observer, I’d say that you've done a few stories that are perfect.

Eisner: Well as we say in the Bronx, “From your lips to God’s ear.”

JWR: In the 1950s the authorities attacked comics as being too violent. Today, video games are being attacked in the same way. What do you think about that?

Eisner: I think about it the same way I thought about it then: It's nonsense. Video games are an outlet for kids. Yes, it would seem we’re living in a more violent society now. But we used to come out of cowboy movies running around the street shooting each other in the "good ol’ days.” I don't think we should close down video games; I don't think we should edit them. I think they should go their course.

JWR: Is there anything that you'd like to saying closing?

Eisner: I enjoyed doing Moby Dick. It was fun.

JWR: So after all this time, you're still enjoying it?

Eisner: Oh, yes. I don't believe in retirement. Retirement is for people who are lying in their graves.

JWR: Or for people who don't like their jobs…

Eisner: Well, they shouldn't retire. They should quit and do something else. I'm still trying to get the brass ring; I still want to produce the work that's perfect.

JWR Leonardo da Vinci said that the great artist was the one who is never satisfied with his work.

Eisner: That's true. And since were quoting people (laughs), Rembrandt’s dying words were, "There's so much yet to do."

JWR: If it's any consolation, as a less critical observer, I’d say that you've done a few stories that are perfect.

Eisner: Well as we say in the Bronx, “From your lips to God’s ear.”